MALL CORE AND NOSTALGIC RETAIL DESIGN: REFLECTING ON THE VAPORWAVE AESTHETIC

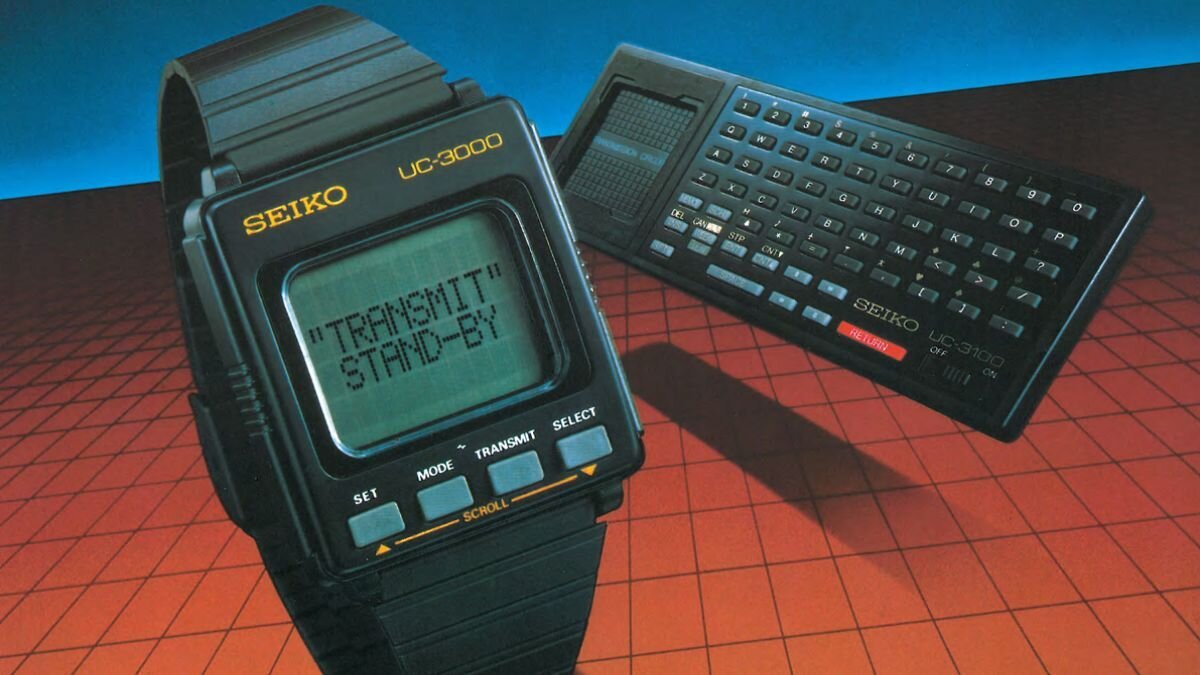

Vaporwave is a subculture and digital art movement of the internet that is difficult to define. It’s characteristics include nostalgic media formats, 1980s retail design, washed out color palettes, and reverbed, forgotten city-pop records from Japan.

This article is part of the on-going series “RAMCPU for sabukaru”. Examining the intersection of art, information and aesthetics, RAMCPU shares his uniquely critical perspective on contemporary art and media to shape the discourse between various discipline and schools of thought.

Vaporwave started to blossom around the early 2010s; and like all new things that are difficult to describe, some people’s explanations of what the Vaporwave phenomenon was were indeed a bit dismissive. Internet users were quick to proclaim that “Vaporwave is Dead” or that Vaporwave is “just a meme” yet these classifications failed to give the stylized genre a place in the history of important and meaningful art movements of modern history. If examined properly, Vaporwave can actually enhance our lives.

When Vaporwave is dismissed as a “meme”, it fails to fully encompass what Vaporwave is and more importantly, fails to acknowledge the potential Vaporwave has to be.

“Memes” and the subculture of Vaporwave do have a significant relation, but generally, it is better to acknowledge Vaporwave as a lifestyle approach or design philosophy, at the very least.

If newcomers to Vaporwave simply understand it as a meme then it tends to solely become a utility for sharing information. Without an ethos and intent to contextualize this genre within the other great movements of history, Vaporwave risks being dismissed as a joke by those who are not equipped to immediately understand its design language.

Though Vaporwave is relatively new, it isn’t a trending meme. Vaporwave is an acknowledgment and revelation of the postmodern era as it promotes a slow and thoughtful reflection on modernism that can be experienced in isolation. As a result, its popularity can be enhanced even in an era of social distancing. Additionally, the genre is strengthened by its ability to trigger reflection in the viewer, since the many pop-culture graphics it references help creating a feeling of nostalgia that jogs our collective memories and reignites our telepathic abilities.

Vaporwave tends to dissolve social class structures, as it makes the archival practice accessible and instead focuses on the commonality between all diverse groups. It emphasizes that there was a shared, forgotten past among east and west, and even in the increased speed of technology and business; there is a common desire for slowness, while meditating on our fondest memories.

While there are many subgenres and styles of Vaporwave, there is a common emphasis on life in a city or metropolis, industry, as well as an emphasis on reverbed and slowed soundscapes that reinforce the following notions:

1) Slowness in the city is to be desired (if not necessary).

2) The desire for slowness should be (and is) an accessible and common interest among people.

3) The interest of the slowed and ambient soundscape can and should influence design methods in the real world, as well as the arts.

Oftentimes, the “mall-soft” sub-genre is most prominently compared to elevator music, since the soothing, non-intrusive, meditative mall-music was intentional in commercial spaces. Through this art form, we are reminded that common places in cities and suburban areas should be calming, and in some cases, as neutral as possible.

This neutrality hints at the blank space of endless opportunity in the minds of young city-goers. Vaporwave often points out that in the child’s mind, the city should function as a neutral, peaceful, and historical facility for reflection. Vaporwave is the place online where people can share memories about what was important to them, they can find out why those memories were important and how those memories can influence a better design philosophy for our future. Great malls inspire us to believe that commercial forces can be compassionate to buyers through utopian and ambient design.

No longer the days of excess. Long live the days of sustainability and calmness.

The way that much of the youth might arrive at philosophical discourse in the postmodern era (or perhaps the “metamodern” era) will be in the analysis of corporate and industrial expansion.

Often, the infrastructures that shaped the cities were the supreme model for excellence. They were examples of creative boundlessness. The ideological impact of these structures, however, went largely unexamined by people who inhabited them. As a result, these structures became like ghosts, especially in their demolished and abandoned state. Architecture was only seen and utilized, but without any true acknowledgment of their significant cultural impact, they became relatives of exploitation.

The Glass House by Bruno Taut, Cologne Werkbund Exhibition, 1914. Interior view from the lower part of the cascade room with the oculus to the exhibition hall visible at the top of the cascade.

Taut’s brochure credits the many artists, artisans, and companies that provided the experimental construction materials, glass prisms and brick, stained glass, metalized ceramic tiles, glass globes, and other new uses of glass and concrete documented in the installation views illustrating this essay. (Exterior Pictured Below)

Today much has changed. With the collective consciousness that is the internet, the Vaporwave movement has evolved itself to the true dreamlike state. Beyond space and time, beyond nature or city structure, truly ethereal, truly beyond.

Vaporwave allows us to see the potentiality for the perfect city. This vision and possibility of an urban utopia no longer belongs to the distinguished academics or masterful architects.

It belongs to everyone.

“We live for the most part within enclosed spaces. These form the environment from which our culture grows. Our culture is in a sense a product of our architecture. If we wish to raise our culture to a higher level, we are forced for better or worse to transform our architecture. And this will be possible only if we remove the enclosed quality from the spaces within which we live. This can be done only through the introduction of glass architecture that lets the sunlight and the light of the moon and stars into our rooms not merely through a few windows, but simultaneously through the greatest possible number of walls that are made entirely of glass- colored glass. The new environment that we shall create must bring with it a new culture”

Bruno Taut’s Glashaus at the Werkbundausstellung in Cologne, Germany, 1914

About the author:

RAMCPU is a writer, philosopher, and creator of the media theory known as Arcadism. RAM writes about media, art, arcades. and internet subcultures.

His weekly newsletter is entitled "Arcade Press".