The Urban Dystopias of Yoshiaki Kawajiri

Urban life is perhaps man’s greatest invention, and as such, they are man’s greatest shrine to himself.

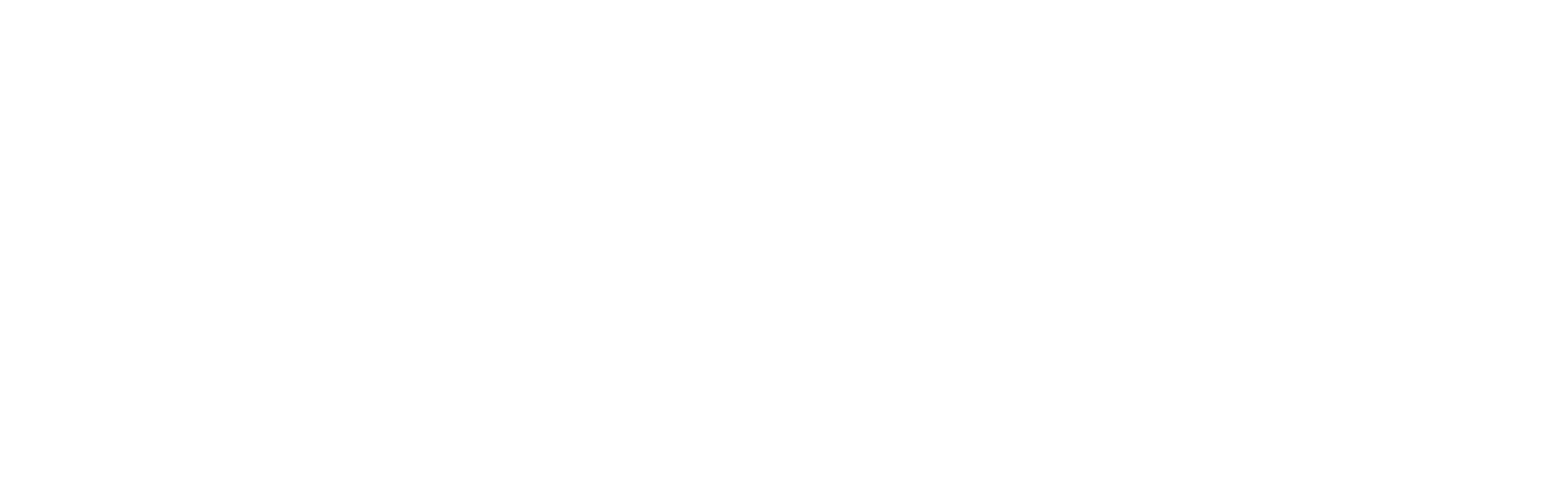

This is the bravado that ricochets down the alleys of the sprawling cityscapes of Yoshiaki Kawajiri’s work. Notable for his egregious violence, taboo style, and determination to shock, Kawajiri is a director captivated by the interplay of characters and the spaces that enclose them. Ninja Scroll (1993), arguably Kawajiri’s best-known title, is but a flagship film bearing behind it an infinitely more flavored repertoire. Stepping behind the curtain of his work, there is a sinister urban infatuation that inextricably links much of his films. Wicked City (1987), Demon City: Shinjuku (1988), Cyber City Oedo 808 (1990); Kawajiri is clearly obsessed with the otherworldly side of the metropolitan. There is a recurrent, and prominent truth to his work; that society's flaws will come to light in the harsh glare of a city.

Kawajiri is a director preoccupied with the flawed nature of the human condition, and he leverages his visual language to communicate this motif through the very composition of his metropolises. His urban spaces are harsh, and cold, metallic not only by touch but in nature, and yet amid his futuristic cybernetic aesthetic, there are warm, carpeted, spiritual spaces where flesh meets metal, where humanity confronts urbanity, where good meets evil. The characters of Kawajiri’s work are oftentimes secondary when observed through the lens of their environments. In their surrogacy, the inhabitants of Kawajiri’s urban dystopias grant the audience brief glancing echoes of the darkness threaded not only through their underbellies, but through the fabric of human nature itself. Arguably, Kawajiri’s cities are the most important aspects of his work; the true catalysts of his stories, the purveyors of his themes, and the executioners of his characters. The cities of Yoshiaki Kawajiri are both the product, and purveyors of the sins that characterize the stories that call them home. In order to best understand these urban hells, we wanted to take you through each iteration of a Kawajiri city, and showcase how each is more perverse, and captivating than the last.

Wicked City

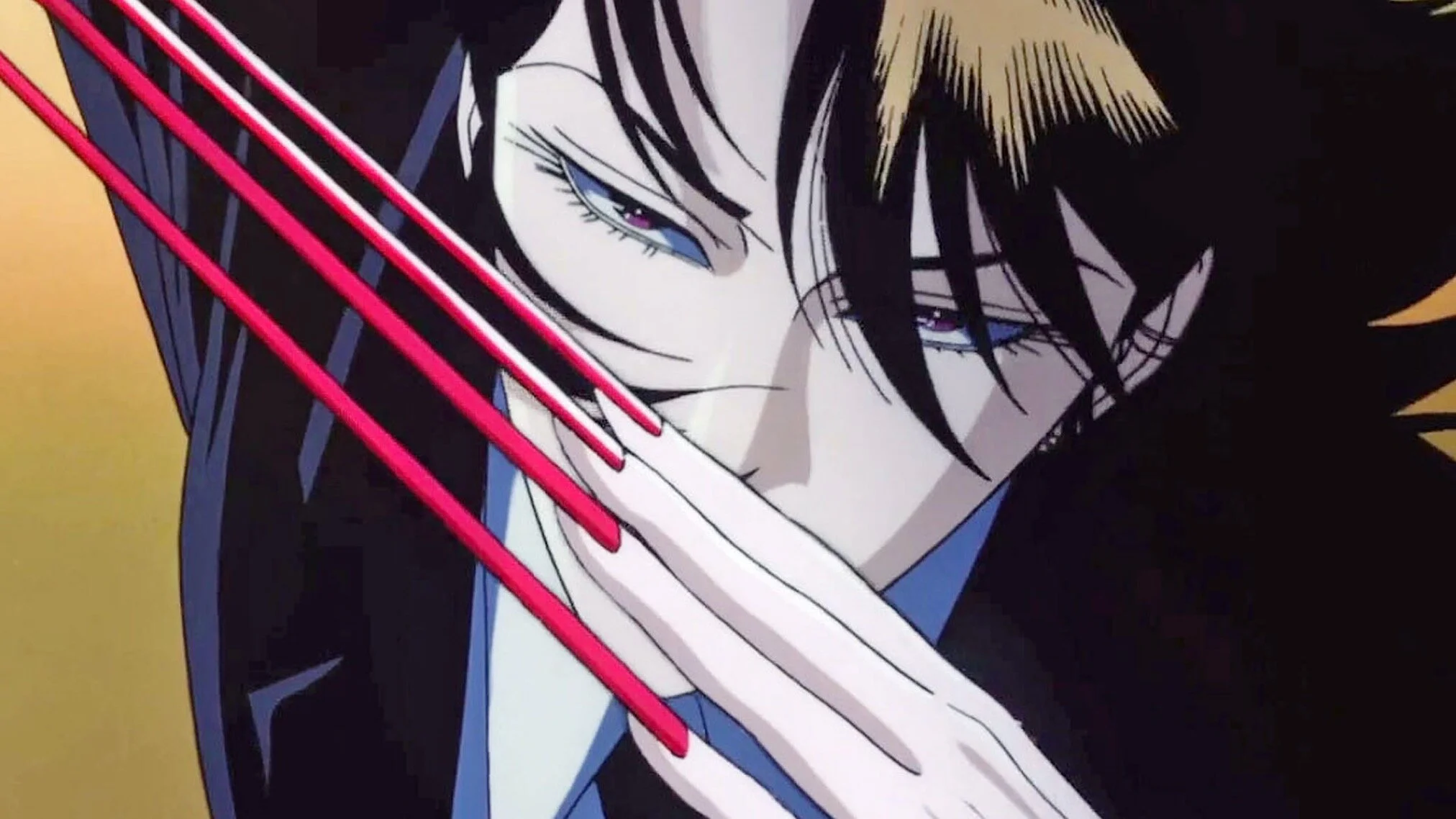

Wicked City, Kawajiri’s 1987 directorial debut, is a film at the mercy of its environment. Based on the Black Guard book series, Wicked City charts a long night of demonic horrors, and violent pursuits in which Renzaburō Taki; career-man by day, member of the Black Guard by night, along with Makie, a demon from the Black World, face increasingly devilish foes set against the blue glow of a moody, midnight Tokyo.

Make no mistake, Wicked City is a graphic victimization film, and it owes much of this to the wickedness of the city in which the story finds itself. The film simmers with an undeniable discomfort, constantly one-upping itself in terms of both sexual and physical exploitation. It skirts the line of thriller-porn at every conceivable opportunity, indulging in raw sequences of overt, graphic violence.

It is an obscenity in excess; the complete epitome of Japan’s fascination with dark, misogynistic erotica. From the lacquered surfaces of the bars, to the bright glare of the massage parlours, the Tokyo depicted in Wicked City, pulses with life. The city itself is bathed in a hypnotic blue-red dual-tone, vacillating between cool, icy neon blues and deep, visceral reds. The film’s dichotomy of color further illuminates the dichotomy of character, and space. Just as the city informs its inhabitants, the characters of Wicked City likewise inform the urban space that houses them. Characters like Taki, and Giuseppe show flagrant displays of permissiveness, and at each interval, the city itself seems eager to accept, and punish them for these carnal desires. In this way, the Tokyo of Wicked City, and its inhabitants seem locked in an endless loop of cyclical indulgence, and retribution.

Time and time again, we are reminded that the Tokyo we see before us is anything but real. The city is characterized by a pervasive sense of anonymity, and temptation that is waiting around every dark corner. This idea of temptation, this indulgence in one's carnal desires, is what comprises the horror of the film. As such, the setting of Wicked City itself becomes the manifestation of man’s dark indulgences. Unlike many other depictions at the time, women are the focal point of horror in Wicked City. They are fatal seduction, given form.

The film takes men’s perceived images of women’s bodies, and contorts it into fetishised horror. It’s no mistake that our playboy protagonist, Taki, is usurped and almost eviscerated by a female demon at the beginning of the film. The men of Wicked City exhibit a shameful lust, fueled by salacious desires, while the women, the object of these desires, are oftentimes their executioners. Indeed, the characters of Wicked City are continuously punished for their lustful desires; even the punishments themselves being sexually explicit in nature. Kawajiri’s debut is perhaps a moral commentary on prejudice, gender, and repressed, regressional temptation. His commentary is ambiguous, to say the least, but it is this complexity that encapsulates the allure of the film.

The Tokyo depicted in Wicked City is taboo, and controversy brought to life, and as such, the film is flawed and at times uncomfortable to watch. To this day, it has a reputation that precedes it. It’s a melting pot of edgy ideas that blend and coalesce to give form to an incredibly stylish, and audacious enterprise. Kawajiri uses the city of Tokyo to bring to life the moral ambiguities of lust. Between the film’s moments of explicit profanity, however, there are instances of genuine moral interrogation and reflection. Wicked City is a sleek, dark exploration of fear, and sexuality that uses the urban space to confront humanity’s dark indulgences, and the resulting horror of this confrontation.

Demon City: Shinjuku

Released in 1988, Demon City: Shinjuku toys with the same concept of the urban space as Wicked City. The city itself is entirely informed by the interplay of aftermath, and ignorance. In an alternative depiction of Tokyo, the city of Shinjuku has been destroyed by a catastrophic battle between former friends, Rebi Ra and Genichirou, descending the surrounding area into a wilderness of feral, and bloodthirsty demons. The film follows Kyoya, Genichirou’s son, as he attempts to usurp Rebi Ra’s grip on Tokyo’s underworld.

Demon City: Shinjuku is a film with a sarcastic self-awareness. The over-the-top theatrics, the killer 80’s synth that pulses under its skin, the film has all the makings of a nostalgic fever-dream. It has a saccharine quality that sticks to you after the first watch and draws you back in for another bite of its elaborate production. The film’s focal points are not it’s deep, philosophical points of view, but it’s captivating, and alluring depictions of Tokyo.

Kawajiri’s style bleeds through every frame of the film. From its opening moments which see Rebi Ra, and Genichirou clash violently, obliterating the then vibrant Shinjuku, to its later scenes where Kyoya enters the now dark underbelly of this war-torn suburb, the entire film hinges on it’s setting. Much like Wicked City before it, Demon City: Shinjuku uses the urban space as a mirror held in the face of humanity. The film is just as much about Rebi Ra’s destruction of Shinjuku as it is about society’s collective ignorance towards it.

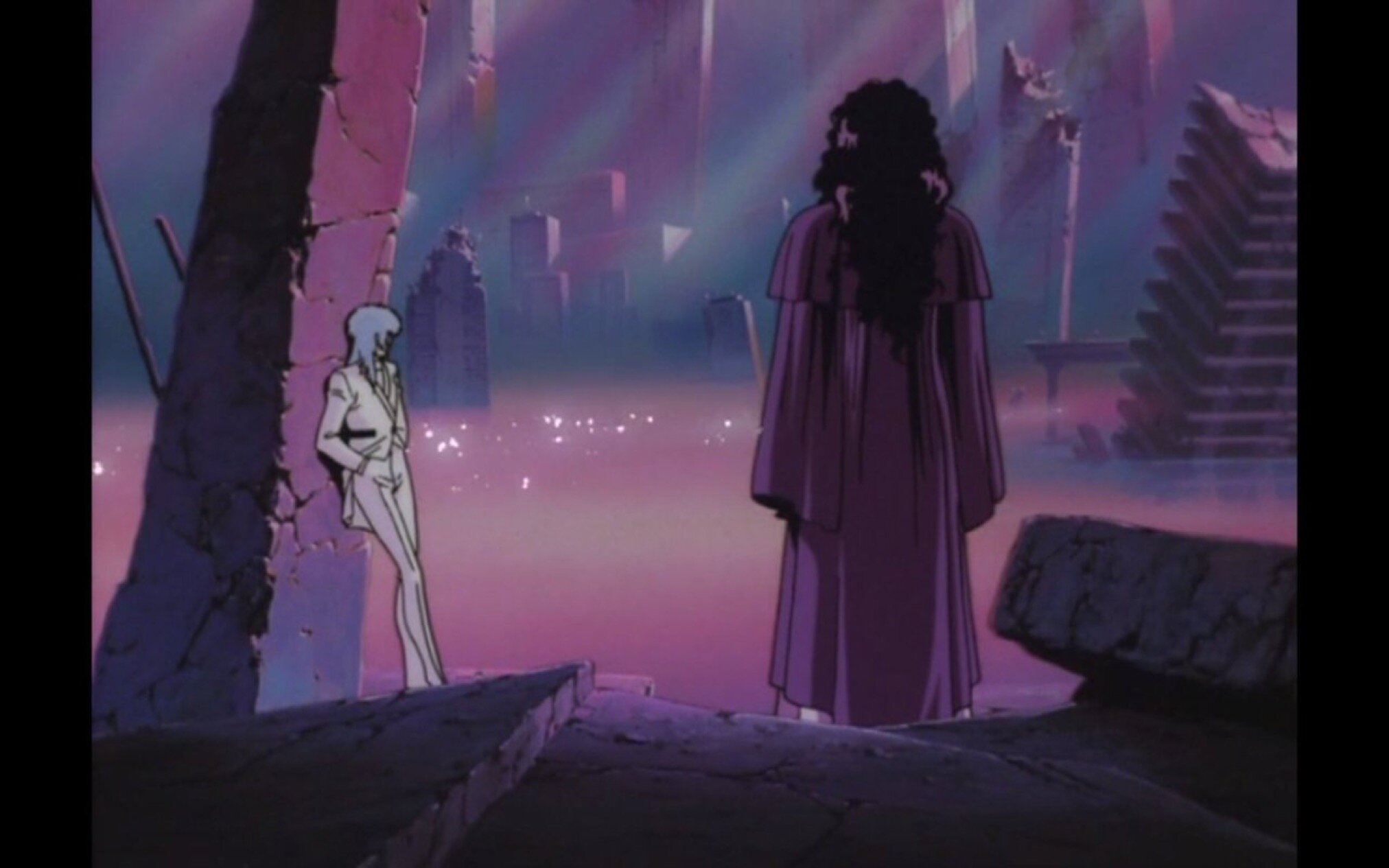

Kawajiri’s depiction of Tokyo is once again the star of his film. Characters and dialogue are disconnected and often crumble under the weight of their own thematic undertaking. Like neon paint rolling in a glass jar, Kawajiri’s Shinjuku shines through the oftentimes skeletal quality of the film. When Kyoya enters the city, he is immediately met with a series of unnerving, and ghoulish opponents. In this way, Kawajiri succeeds in painting this forgotten landscape with incredibly haunting brush strokes. The urban hell of Shinjuku emerges from Kawajiri’s intersection of aftermath, and ignorance. As Kyoya enters the city, there is a pervasive sense that all hope has been lost; as if is passing through the gates of hell in Dante’s Inferno. Rebi Ra’s wrathful occupation has dismantled the city entirely.

Something sinister is constantly disappearing around the corners of buildings, warning us that what we are witnessing should never be seen by anyone. The aftermath has left the ruins of the city harsh, and oppressive. It’s a fascinating juxtaposition to the Tokyo we see during the first half of the film. The inhabitants of the greater Tokyo are satiated by their banal lives, and there is a sense that what has occurred in Shinjuku has been forgotten entirely. As such, the hellish demons occupying Shinjuku can perhaps be thought of as the manifestation of society’s willful ignorance, and the sustaining factor of the city’s destruction.

Demon City: Shinjuku suffers from its dull pacing, and lifeless characters, but these sections are punctuated by the thrilling, and electric portrayal of Shinjuku as an environment. The film, like Kawajiri’s previous work, uses the city as a metaphor, and reflection of humanity as a whole. While Wicked City cast it’s glare on lust, Shinjuku illuminates humanity’s ignorance and the repercussions of this willful ambivalence.

Cyber City Oedo 808

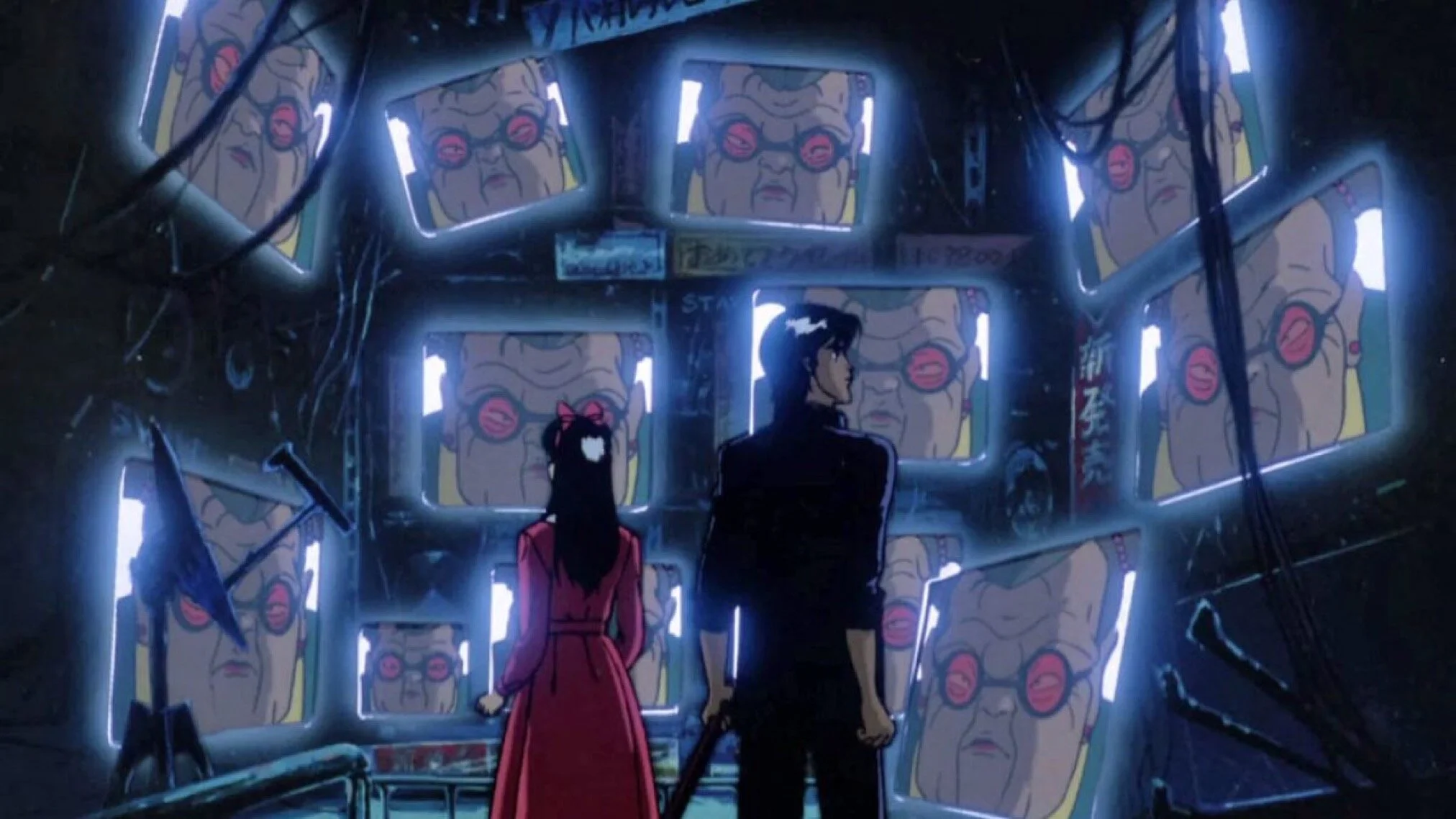

Cyber City Oedo 808 is a departure for Kawajiri not only in form, but in substance. Unlike Wicked City, and Shinjuku before it, Oedo is granted the luxury of exploring it’s world over the course of three hour-long episodes. Furthermore, it is immediately apparent that the cyber city of Oedo is unlike anything we have seen previously from Kawajiri. Set in the year 2808, society has advanced exponentially in terms of technology. The skyline of Oedo is characterized by oppressive, obelisk-like skyscrapers intersected with flying aircrafts that its inhabitants use to navigate the harsh metallic horizons of the city.

Society’s advancement has brought with it, however, a brutal degradation of human life. This is showcased in our protagonists; Sengoku, Gogol, and Benten, three criminals with prison sentences of over 300 years each. Our protagonists have been commandeered by the cyber police to work as officers in exchange for the lessening of their respective sentences. Should our protagonists try to escape, or fail to complete their missions, their explosive collars will be detonated. The police chief himself is so morally ambiguous that he uses that threat of detonation to mobilise them. The entire city of Oedo balances on a knives edge; teetering on the precipice of a complete loss of control. As such, Kawajiri uses the urban space in Oedo to examine the moral ambiguities of the human condition, and the complexities of good versus evil.

Oedo exists between several thresholds; that of good and evil, black and white, right and wrong, and this is showcased in the concrete greyness of the city itself. The protagonists of Oedo are likewise characterized by a moral greyness. Sengoku, Gogol and Benten all display behaviour that would otherwise be classified as “good” in their respective episodes; Sengoku even gets punished for his kindness. Kawajiri wants us to understand that they are not necessarily bad people but caught up in an unjust, unforgiving system.

The people in charge of said system, however, are perhaps the most morally corrupt. The Cyber Police, as well as the Military Special Forces, play a prominent role in the series, if not only to act as the moral foil to our protagonists. In one particular scene during Gogol’s episode, the chief of the Military Special Forces ironically remarks of the growing lawlessness of the city, to in turn become the sole catalyst for said lawlessness later on. As such, in Oedo, it becomes difficult to decipher who the real villains are, almost as if Kawajiri is questioning whether heroes, and villains exist in the first place.

This moral ambiguity extends itself far beyond our central cast of characters. In Benten’s episode, there is a sequence within which he interrogates several inhabitants of the city, all of which appear to be hardened criminals, or at least caught up in the dark underbelly of society.

The city seems built upon a self-sustaining ecosystem of criminals, as our protagonists come face-to-face with past friends, turned targets, throughout the series. There is a depressing reality to the self-preservation of the characters of Kawajiri’s Oedo; almost as if criminality is the key ingredient to survival in this cybernetic dystopia. Glimpses of normal human life are few and far between, and Kawajiri’s choice to feature criminals as his protagonists is indicative of the environment that produced them. Ultimately, Oedo is a story about characters striving to reclaim their lives in the midst of a cybernetic dystopia, as our protagonists reminisce about older times. However, akin to the city itself, there is no turning back for our antiheroes, as their vestiges of humanity have been made frigid, and bleak by the hands of time.

Cyber City Oedo 808 is perhaps Kawajiri’s greatest and most beautiful metaphorical undertaking. The moral ambiguity of the city permeates the lives of its inhabitants, shrouding everyone and everything in a perpetual greyness. Unlike Wicked City, and Shinjuku, Oedo is Kawajiri at his most mature; tackling the enigmatic nature of the human condition. The three-part series is florid, unforgiving, and deeply moving to observe as a viewer.

Yoshiaki Kawajiri’s fascination with the urban space is among the most tantalizing in all of anime, and perhaps beyond. His work is weaved with classic elements of cyberpunk, yet bolstered with indulgences in graphic bloodshed, and intrinsic horror. Unlike many of his contemporaries at the time, Kawajiri’s work is characterized by his thick, and frequent violence, as well as his overwhelming determination to horrify. His focal themes; those of lust, ignorance, and finally moral ambiguity, are brought to life in the metaphorical architecture of his cities. The city as a visual metaphor is not something new to cinematic media, in fact, it is a common tool leveraged by some of the most acclaimed directors in all of film. See Ridley Scott’s Bladerunner.

However, there are few iterations in cinema that stack up to the latent symbolism of Kawajiri’s genius. His environments live and breathe, and there is a quiet, yet powerful, kinetic exchange between his characters, and their setting. The symbiotic relationship that Kawajiri establishes is one of inherent awe, and intrigue. Just as his environments lure and ensnare his characters, Kawajiri’s films beckon the audience inwards, further down the rabbit hole of his sophisticated, yet putrid collection of films.

Urban life may perhaps be man’s greatest invention, however, Kawajiri’s work demonstrates a determination to evoke the darkside of urbanity, that ultimately invokes the darkside of humanity itself.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Based in Dublin, Kieran Enright writes about all forms of art, media and culture that exist on the fringes of society.