Constant Practice - Meet Fashion's Most Unique Archive

“THE FUTURE IS IN THE PAST” – a statement labeling Nigo’s just-bygone archive exhibition at the Bunka Gakuen Garment Museum says a lot about how creative processes are oftentimes approached. A thought initiates numerous routes for individual understandings – pathways that would eventually lead to varying creations due to variables in cultural background and individual application. Yet, with the tendency of not reconsidering but simply recycling what has been popular, we’re confronted with questions of impact and time. How do we separate sustainable impact in design from a short-lived fad? Why do some designer pieces achieve the label of timelessness, whereas others remain stuck at a specific point in time? There’s a lot to consider, and the past is most likely the heart of the matter.

With the rise of the digital age, the act of curation has received significant popularity, not only because online platforms broke down barriers but also because they facilitate engagement with people of similar interests – as odd as they may be. Whether it’s someone passionate about movies or someone that enjoys showcasing his record collection, there are uncountable opportunities for individuals to share their passion and strike up conversations with like-minded people. And it’s particularly these democratized conversations that, in the best case, not only introduce but also include newbies who formerly just scratched the surface of an issue.

In the matter of clothing, “archival fashion” has risen to prominence in bygone years. The term “vintage clothing” does represent the idea in parts, yet it doesn’t tell the whole story. Whereas archive pieces can simply be described as designer items from earlier seasons, the archivists are the ones who eventually give the term its purpose. As archiving is about the preservation of historical data, the accumulation of documents allows a bird’s eye view of the trajectory of a designer, a certain period, or even fashion as a whole. Thus, it illuminates the missing pieces to the puzzle that make us understand where an idea originated, what impact it had and why it might be important today. Summarized, it’s a commitment to research necessary to comprehend the past, present, and future.

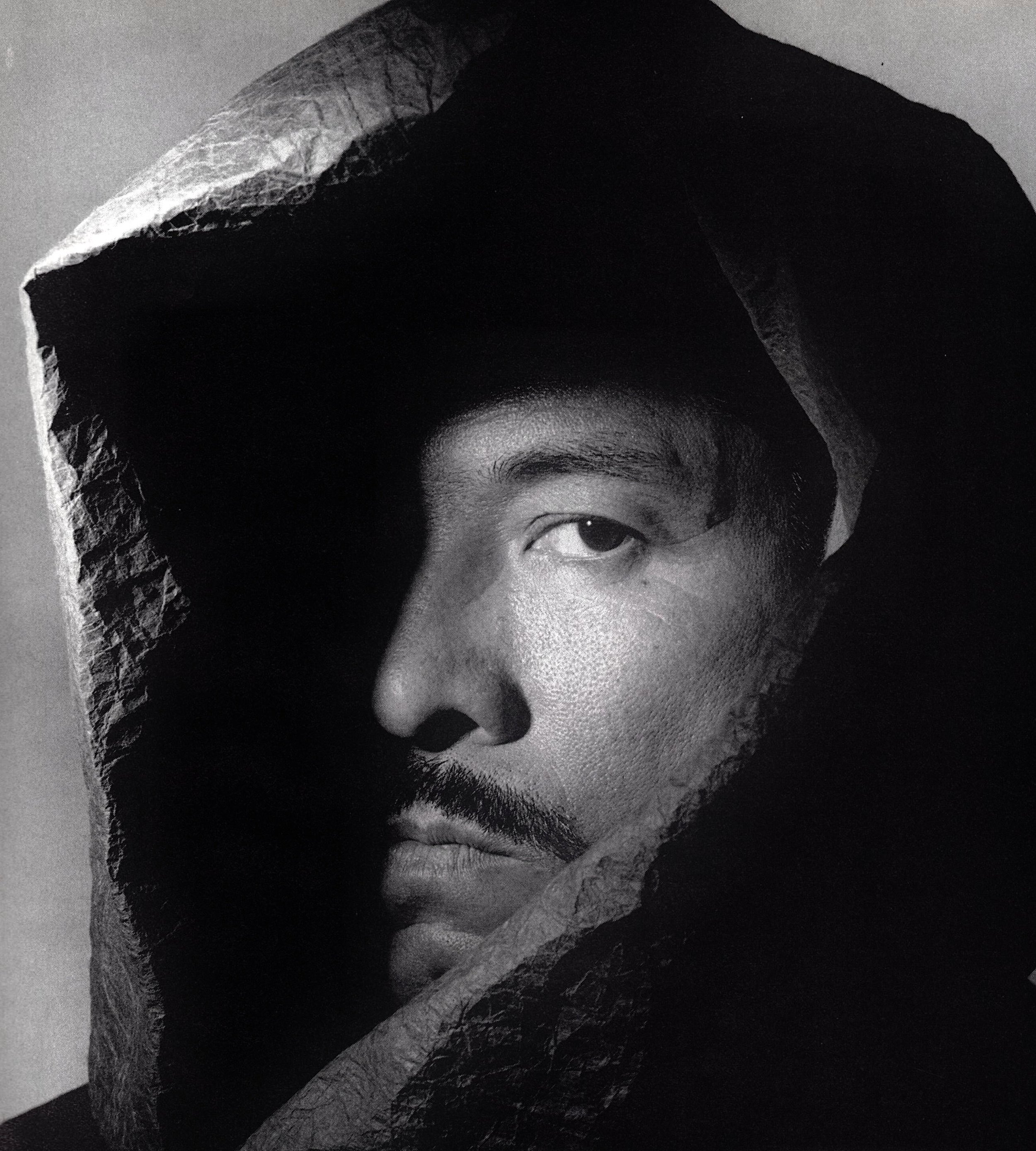

Nigo at THE FUTURE IS IN THE PAST exhibition

At the same time, fashion archives have become a sought-after business model offering exposure to or consumption of pieces that are widely obscured – either because they’re hard to find or because they’re long forgotten. Either brands seeking inspiration for their latest collections or people who love timeless design, archivists are the addresses to reach out to. While many started as pages on Grailed, buying and selling designer clothing as a hobby, a handful of sellers made a name for themselves through a unique perspective internalized in a striking selection of rare designer garments. One of the most successful is Zeke Hemme, the man behind Constant Practice. Having transformed his side hustle into a business, Zeke’s curation can be described as a design-driven exploration of various fashion eras. From Japanese avant-garde masters, revolutionaries in functional design, praised talents of the contemporary, and labels that are still under the covers, Constant Practice constructs an umbrella under which all these innovators create a coherent image. And speaking of images, the way he and his partner Jonah portray the items is arguably as peculiar as the whole selection itself. We had the pleasure of sitting down with Zeke and talking about his early beginnings, his perspective on Constant Practice, and various other topics.

Constant Practice is undeniably one of the most regarded addresses for archive clothing And up-and-coming Designers. But for those who have never heard, could you please introduce yourself to the Sabukaru network?

I’m Zeke Hemme, and I’m the owner. We have one employee called Jonah, the guy you see modeling everything now. Previously it has just been me in the office just taking a fit pic in the mirror, and it gradually grew bigger. What we’re specifically doing has changed over the years. We essentially provide consulting services, or inspiration for brands and individuals, whether it’s someone who’s just starting out or a company that wants to see some designs from brands that aren’t necessarily talked about anymore. I hope that’s a decent way of describing it. In general, we’re trying to take things not too seriously, as you guys can probably see in the content we do. It’s a great juxtaposition to showcase this stuff by giving it some context in the way it can be worn instead of being extremely serious about it. I geek out on all our stuff, about all the details most people might not think about. And so is Jonah. We’re two peas in a pot that talk about stupid stuff and show it in videos and photos. It’s a fun passion project that has grown into a business, ad we’re just trying to figure out how to continue. There’s all that kind of serious and non-serious stuff going on.

When and how did you come about with the idea to start an archive clothing business? when did you put it into practice?

I’ve been selling clothing since 2015-ish, I would say. Around that time when Grailed popped up. That was when I started it. And then, since 2019, I have followed it as an actual business. And in November this year, I quit my job finally. I’ve been an IT-Consultant for seven years which was a way to pay bills and all the fun stuff on the side. So I stuck on all the income and benefits from my previous job and gradually grew the clothing business. Since 2019, it’s kind of been its own thing. I started dealing with some archive stuff from Yohji Yamamoto, Issey Miyake, and maybe a little Comme des Garçon, but it transitioned into something completely different now, which feels much better. I’m just figuring out what to do next and what brands or products to sell.

How did you come up with the peculiar bathroom setting that people associate with Constant Practice these days?

It has changed over the years. Under 50k followers on IG, I was just doing flats on a tarp. In the current space, it probably took me three to four months to figure out the new setup for photos. We tried a couple of things, and it was basically a trial-and-error process. Everything that we approach is a trial-and-error process. If you look at some of the earlier reels, they’re pretty shit, and that’s just kind of figuring out how that all works. And once you come to the point where you find out what the bread and butter is for operating, everything falls into place, from the setting to planning out products. What’s probably the hardest for many people is taking the first step. They want to be prepared initially, but I learned over the years that you just need to do it, and then you’ll start sorting it out and eventually become better. For example, some of our reels were really long, but now they are not longer than 10 to 15 seconds. It’s a fine line because there are certain things that you know will work really well, like a popular item or some sort of detail that people love. But sometimes, we also want to be a little more serious and provide some more context, yet a lot of the stuff we’re curating informs a lot without saying a lot. So, we’re not trying to be too wordy and don’t want to phrase the same unique details of a designer repeatedly, as people see that for themselves.

AW2003 iDiom Aviator Headphone Cap

Your shop doesn’t only stock archival materials but also items from well-established contemporary designers. Furthermore, you have included pieces from brands that are still widely under the radar. Please tell us a little about your curation. Do you follow a certain strategy in the brands that you stock or is what you find in the lookoff?

It’s kind of what I find in the lookoff. A strategy is something that I would like to spend more time on, but it comes down to not having enough time to do everything. So, Per Gotesson is the first obscured brand that we stocked. I’ve seen a couple of his pieces in stores, and I saw that certain pieces of Per’s fit well with our design language as it’s pushing the design envelope. I’m pretty into design, you could say. I think it’s more or less about how you approach the overall design in a way that feels true. So, if you’re taking archetypes like an M-65 field jacket, you see brands capable of interpreting it in a way that pushes it further. They’re taking certain elements from ideas and applying them to different things. They’re tweaking it, and that’s what makes it feel different and maybe weird, but you still have a lot of these core design elements that ground it. It makes it feel new, but at the same time, it doesn’t, and that’s what facilitates the piece’s timelessness. I think about Girbaud pieces as completely timeless as they own a unique design language that doesn’t make the pieces feel gimmicky.

With regards to Per, he’s bringing out a lot of interesting pieces, but I’m very selective about buying and putting them in a store. So we just pick certain items as they fit great to the store’s aesthetic, and that’s the opposite of what many stores do. We tend to pick a few things, and then we move on. The same thing goes for Seeing Red. I think Seeing Red does colors incredibly well, as it’s challenging to put five different colors together and make it feel cohesive. Fred does a good job as he has his own design language. And that’s really hard, coming up with something no one has done before. Everything Seeing Red feels very Seeing Red, whatever he does with it. Whether it’s the colors he chooses or the way he finishes garments. It feels really complete, and that’s why we like it so much.

Jonah in Seeing Red

Same for Bryan Jimenez. He has an aesthetic that is very concise. It feels like a mix of Rick Owens, Helmut Lang, and some other products that we sell in the store that are in that lane. The idea for those newer brands is to make them fit with the other parts of the selection and that informs the brands we bring in. At least we’re trying to push that more than before. So we’re trying to transition it from the usual archival scene, like Yohji and Issey, to a point where it’s mainly about aesthetics and design and not merely the brands – like a moodboard for aesthetic and interesting designs.

Your curation predominantly consists of thoughtful explorations in design, displaying loads of clever ideas, whether practical or merely playful. Yet, how important do you consider the cultural or historical components when looking at pieces?

Previously, with the Yohji and Issey stuff, it’s us providing the historical significance which comes from an expansive catalog of products. I like to think we do a good job picking which ones are actually worth their price, and that comes down from having over 200 pieces from a brand like Girbaud. And out of these 200 products, we sort out which ones have the highest complexity, whether it’s the idea behind the design or its execution. Furthermore, we’re looking if it fits in the space of the current fashion climate, so by looking at trends, we can sense whether an item is likely to sell or not. At the same time, it has to fit in the space without any explanations. Like the piece we listed today, it just fits in. We don’t have to do anything. You could probably throw it on right now, and it feels like someone has just made it. Basically, it’s providing people with the right items based on what they’re looking for and also having a vision for the store’s curation. It’s a balancing act between the two.

The attention around Constant Practice seems to stem primarily from your garments’ unique curation and portrayal rather than their high exclusivity. Could you describe how your taste developed over the years?

There are two parts to that. The buying for the store and the buying for myself. Buying for myself is much more reserved. I had my peacock phase, my weird silhouette phase, like Yohji Collettes. I’m much more functional-driven now for the sake of wearability. I have kids, so I just got to get up and go without thinking too much about what to wear. I focus a lot more on color now, and that goes for the store as well. I also think our pieces are more wearable than before. We try to offer products that more people can buy from those brands. So you have your high-tier, mid-tier, and low-tier like in any other store. Furthermore, we’re expanding on the brands for the store from a vintage standpoint. There’s a lot of interest around brands besides the main ones, even though the main ones like Issey, Girbaud, and Hamnett inform me for what I like to wear, brands that I identify with a lot personally. There’s a lot more that I like, like Kiko, for instance, but it basically comes down to a muted palette and a focus on design, colors, and construction rather than mere flamboyancy. We do like doing more showy fits on the feed now. We try to do that every now and then. Something a bit more progressive or products with odd proportions.

Generally speaking, what do trends in fashion mean to you and your work? Do you act according to perceived/anticipated trends? Do you try to predict trends or rather neglect them in principle?

All three. It has changed over the years, but now it’s all three. I’m thinking of it from a business or marketing standpoint. You're trying to hook people in! Following or foreseeing trends is something we have been trying to do, but it's surely not the sole thing at this point. Previously, it was trend-based with all the archival stuff. Initially, I started with Undercover and Cav Empt. Undercover was especially popular in the 2016/2018 era. But at some point, the market became so saturated that I started buying into Comme des Garçon, Issey Miyake, Yohji Yamamoto, and Junya Watanabe. Particularly, the Yohji and Issey stuff, nobody was necessarily purchasing a lot of it despite a few notable pieces. I like to think that it was me forecasting a little bit, but it was also me personally liking that stuff. Probably because only a few were into that at that time. Now I would say it's definitely more about buying what we want to buy and forecasting on our own, which is kinda like gambling, to be honest. All the Mandarina Duck stuff, for example, is probably some of the best wearable, functional stuff in the store. It's obviously really understated. It has this Jil Sander, Helmut Lang, or Acronym feeling to it, as you have to see it in person to appreciate it whereas there are pieces that are louder and easier to be understood online. That's an example of a brand where I gamble a little bit.

Jonah in Issey Miyake

As an archivist, how do you feel about the phrase “The future is in the past?” Do you think that the ability of thorough research enhances better design?

I would say so. My take on this is: "Why should you overcomplicate something that's already been done before?" It's the same approach as what I'm doing with the store as you ask yourself what kind of product fits in today. And if you want to make a product yourself, you repurpose it, reconstruct it, or reference it in a way that makes it feel different instead of making a one-of-one ripoff. For example, by utilizing tiny little details or random things, like a peculiar pattern, and considering them for a product that fits in our time, then you’ll create something that feels fresh. I feel like you move forward by making small changes rather than drastic ones. You slowly tweak certain things, which is why I think Acronym works so well. He's just using a lot of the same patterns, not all the time, obviously, but he's making various iterations. It's really similar to how Katharine Hamnett's business model worked. She did certain cuts, silhouettes, and fabrics and iterated on that. You have your staples, and you build it off of that instead of trying to reinvent the whole thing over and over again.

We are living in a time in Which Instagram moodboards are the main source of amplification, both culturally and commercially. What are your thoughts on digitally curating fashion pieces? Will it become more important than actually owning the pieces?

I think you lose a lot of context that way. There's a lot of feeling and personal identity that comes from wearing the stuff. There are all these characteristics to clothes. There are a lot of reasons why construction workers or people that live in their clothes feel more natural and authentic. I think that's just the lane where I'm. Jonah and I wear the same outfit over and over again. Last week I wore the exact same thing five days in a row. The whole purpose should be to wear the stuff instead of uploading it into the metaverse. I mean, it already happens on Instagram. People take pictures of themselves in clothes they never wear, while people in the 80s and 90s actually wore stuff, and that was actually it. Nobody knew who you were, and you were just doing it for yourself because you liked doing it. Sure, some probably wanted to fit in a little bit, but if you lived in Kansas, nobody knew what you were wearing. In New York, there was at least the possibility of running into someone that may have known, but it was generally simply about wearing stuff.

Jonah in Final Home

Finally, besides being a store, Constant Practice is also an educational platform for many. Do you have a broad vision for the future beyond commerce? Something that may feel far-off but would mean a lot to you personally if it came true?

Continue to sell, and expand on interesting products from interesting eras. Also, build up the branding. We have branding, but it's not blatant, so we're trying to progress in that area. We would like to work with certain brands on some products as well. Whatever they want to do. It could be whatever, either behind the scenes or an official collaboration. As long as it fits with the store and what we're about, we're down.

1980s Armani Tri Tone Iridescent Puffer

Thank you so much for your time!

Senior Editor & Interviewer: Joe Goodwin

Text and Interview Questions: Henry Vieler

Interview Questions Assistance: Mark Gilcher