Enter Keiichi Tanaami’s Psychedelic Dream - An Interview with A Pop Art Master

Keiichi Tanaami’s art is beautiful chaos, partially based off of his darkest memories and the rest- just pure psychedelic fantasy.

Shot by Tsubasa Saitoh

Although contemporary Japanese art has many artists that are “groundbreaking” or “pioneers” Keiichi Tanaami is the real deal, whose work spans collages to animations, and is most renowned for his mandala-like mixed media paintings. Tanaami is truly Japanese Pop Art’s juggernaut- his art is a symbol of America’s lasting cultural and military impact in Japan post- WII. Bringing his dreams as well as nightmares to life, through crowded surrealistic designs full of cartoon and traditional Japanese symbolism.

Photo credit @keiichitanaami_official

If you need a crash course on Japanese contemporary art, Tanaami’s work should be top of your list, alongside Tadanori Yokoo and Takashi Murakami, as the most influential Japanese Pop artists. Tanaami’s work has achieved iconic status for being the first artists to fuse “low-brow” culture -like cartoon hero Mickey Mouse and cut outs of raunchy pin-up magazines alongside the markers of “high art” AKA attention to detail, references to classical symbols, and visuals critiquing the social-political structure of society.

Tanaami was the predecessor to what would later be called the “Superflat movement”, that both celebrated and criticized the emptiness of consumer culture engulfing Japan from the 1950s on. The movement focused on 2-D art designs and elevating otaku culture from the level of “trashy” to a respectable form of creative expression. But even without the fancy jargon surrounding his status as Japan’s most legendary post WII artist, just viewing Tanaami’s work makes you understand immediately his knack for bridging East-meets-West references and the ingenious way Tanaami brings his subconscious to life.

Photo credit @keiichitanaami_official

Born in 1936 and growing up in Tokyo’s Meguro ward, Tanaami’s childhood was bittersweet, much like the simultaneous saccharine and disturbing art he’s known for.

Tanaami’s earliest recollections are of U.S airstrikes obliterating his neighborhood and even some of his neighbors right before his eyes. In between the terror of dodging bomb raids, the whirl of fighter jet engines, the collapse of Imperial Japan alongside the hardships of WII poverty, Keiichi found solace and obsession in manga, B-rate monster films, and the American pop-culture zeitgeist, that made it’s way to Tokyo in the mid-century. With the initial hope of becoming a mangaka himself Tanaami, feverishly locked himself in his room sketching copies of popular characters and reading the works of Osamu Tezuka, the genius behind Astro Boy and Metropolis.

Shot by Tsubasa Saitoh

Keiichi Tanaami’s goal of becoming a mangaka seemed right on track to succeed. By the time he was a teenager Keiichi was taken under the wing of Kazushi Hara, his mentor and an accomplished mangaka in his own right. Diligently focusing on art because it was the only thing he felt passionate about, Tanaami’s path took an unexpected turn, after Hara abruptly passed away. To Tanaami, his mentor's passing ended his chance of becoming a full-fledged cartoonist but not his desire to pay respect to the cartoons that made him want to become an artist in the first place.

Kazushi Hara - mangaka and Keiichi Tanaami’s mentor

Nearing the end of his high school graduation and facing his family's disapproval at following a creative lifestyle, Tanaaami took the leap and decided to study at the Musashino School of Art, graduating with a reputation of beginning one of the most talented students in his class despite seldom coming to his university classes in person.

As a young adult Tanaami also found inspiration within Japan’s Neo-Dada Organization, a collective started by Masunobu Yoshimura of boundary pushing artists, known to stage outlandish raves and art happenings [like making sculptures out of garbage or protesting the U.S-Japan Security Treaty]. Their vision encouraged him to see art as a mash-up of all influences and materials that didn’t necessarily have to please society or make a monetary profit.

Keiichi Tanaami in 1968 - photo credit @keiichitanaami_official

After graduation, following the strict advice of his mother who thought an artists life would lead to “poverty and womanizing”, Tanaami entered an advertising agency but ended up quitting shortly after two years after being flooded with private commissions and finding the work to be “too boring” to stay. Flash forward a couple years, and Tanaami became a sought after artist, creating album covers for Western psychedelic rock bands like The Monkees and Jefferson Airplane as well as design projects galore across fashion-design-and music spectrum.

Tanaami later became the first Art Director for Japanese Playboy, which led him to travel to the U.S. During his time there he came into contact in New York City with The Factory, the art collective/non-stop countercultural party venue headed by artist Andy Warhol. Although the two never talked in depth, Andy Warhol’s bridging of mass consumer culture with fine art was something Tanaami admired and infused in his own work.

Now, Keiichi Tanaami is still doing what he does best, creating visions of beauty and destruction in his Tokyo studio at an astonishing pace. At 86 years old, Tanaami looks serene and even like your favorite uncle; dressed in a simple blue sweater, beanie, and tan slacks, but speaks and works with a clarity showing he has no signs of halting his artistic output.

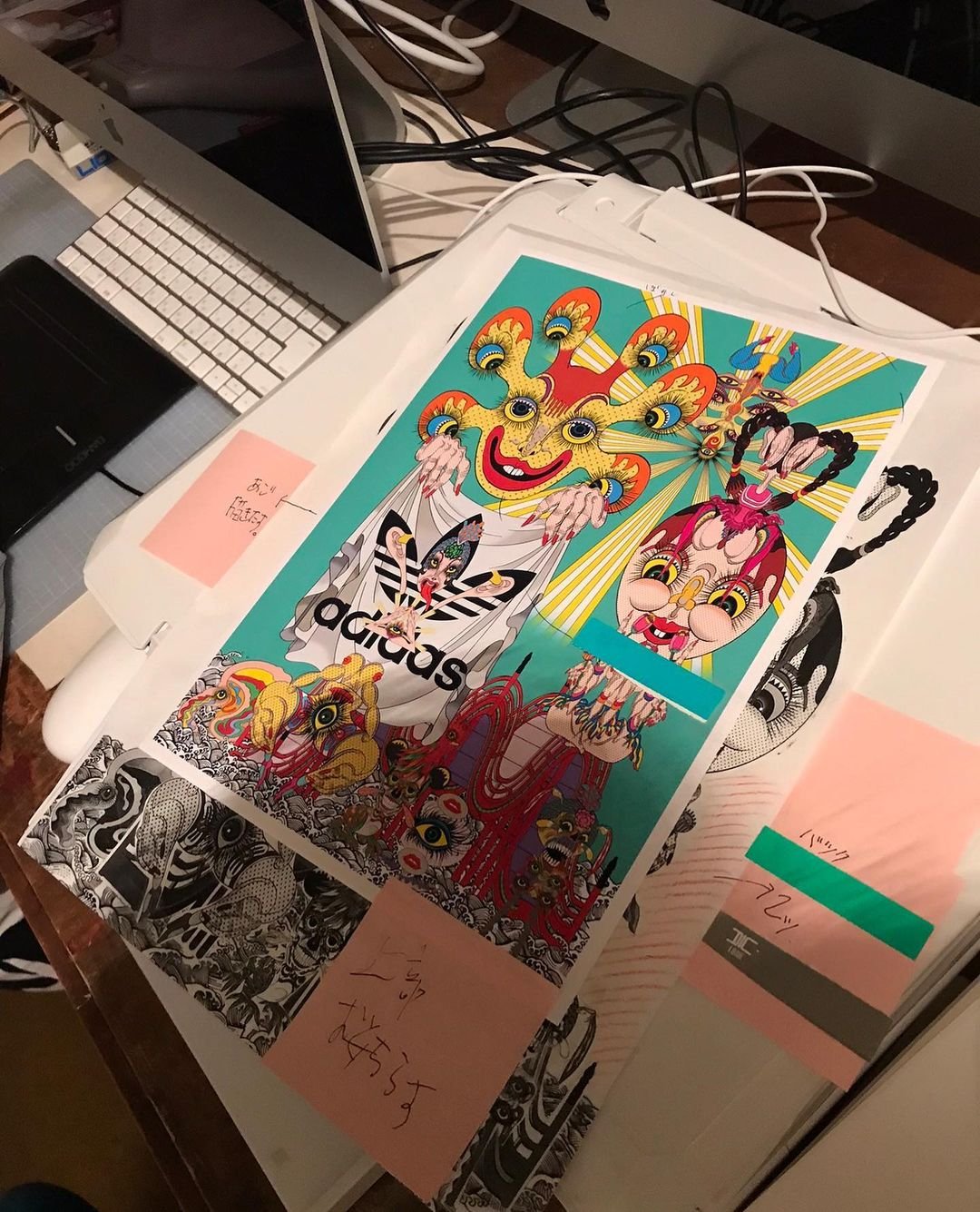

Tanaami’s demeanor is astonishingly down to earth and patient for an artist of his stature. Aside from his solo work, Tanaami has collaborated with brands such as adidas in 2019, resulting in a highly sought after artbook and apparel series featuring the sneaker brands classic trefoil logo with Tanaami’s signature dream-like symbols as well as a Moncler collab in 2006 featuring vivid surreal graphics on their signature puffer coats.

Never one to stay in place artistically, Tanaami in many ways is in a new era of his career. His upcoming show titled “Tanaami!! Akatsuka!! That‘s all Right!!” in Tokyo at the Shibuya Parco Museum opens Jan 21st. Additionally, a new series of Picasso inspired paintings [of course with Tanaami’s own unique twist] titled “Pleasure of Picasso” is on display at THE BRIDGE in Osaka ending on Jan 21st. These pieces arose out of whim, while Tanaami was passing time recovering from a short stint of “artists block”. The result is over 100 pieces inspired and in conversation with Picasso, a fellow boundary pushing artist grappling with the aftermath of war.

Photo credit @keiichitanaami_official

Sabukaru got the chance to sit down with Keiichi Tanaami in his studio, reminiscing about how childhood trauma has inspired his work, what keeps him creative after painting for over seven decades, and why he has little advice for young artists to follow other than “chase your instincts”.

FOR THOSE NOT familiar with your work, can you please introduce yourself to the sabukaru and gata network?

よくご存じの方々も多いと思いますが、sabukaru と gata の読者でまだ知らない方に向けて自己紹介をお願いします。

Shot by Tsubasa Saitoh

I went to Musashino Art University and studied design there. I actually wanted to study painting, but at the time, parents frowned upon the idea of pursuing fine art.

I ended up landing a job at Hakuhodo's advertising agency, but I quit after 2 years of working there since I was also freelancing as a designer, and that was going pretty well. I was freelancing until I was 40, but I found out I had tuberculosis. My doctor warned me I wouldn’t live long if I continued doing what I was doing. Only then did I start painting again, and I’ve never looked back ever since.

Shot by Tsubasa Saitoh

Fast forward to where we are today, I’ve also been producing animations, creating objects, and also collaborating with fashion brands from time to time. The exhibition I’m opening has a variety of things I’ve been working on, from installations to my newest animation work. I can’t put it any simpler, so that’s what I’ve been doing.

僕は東京の武蔵野美術大学という所でデザイン科を卒業してます。本当は洋画の方に行きたかったんだけど、僕の時代はそういう方向に行くのを親が嫌がる様な風潮があって。反対されてデザイン科に入って、卒業して博報堂の広告代理店で就職して、そこで2年ぐらい働いたんだけど、フリーランスの仕事が増えちゃって。それで辞めて、それ以後フリーになったんですね。ずっとデザインの仕事をしてたんだけど、40歳ぐらいの時に働きすぎもあって結核になっちゃったんですね。それで4ヶ月ぐらい日赤病院で入院をして、医者に「こういう生活を続けてるとまた病気になるよ」ってアドバイスがあって.アートの方に一向していったんですね。

Photo credit @keiichitanaami_official

それから現在に至るんだけど、その間絵だけじゃなくてアニメーションも好きなんで、アニメーションの制作もやったり、立体を作ったり、ファッションメーカーと一緒に仕事をしたり、そういう様な事をずっとやってるんですね。今度の展覧会なんかも立体的なものからアニメーションの新作の発表まで色々取り交ぜてるんですけども、簡単にいうとそんな感じですね。

When did you first realize you were an artist? Was it a feeling you had in your childhood or was it a specific moment from later on?

一番最初にアーティストになりたいと思ったキッカケとなるエピソードはあったりしますか?それともアニメーションから始まる幼少期の頃に触れた様々なものが自然とそういう感情を芽生えさせましたか?

Shot by Tsubasa Saitoh

I actually wanted to be a manga artist since I was obsessed with Osamu Tezuka. My father had a famous manga artist as a friend back then, and his name was Kazushi Hara, so I had him look at my sketches, but he passed away because of tuberculosis.

After his passing, I didn’t really know what to do, so I decided to go to art school and continue writing manga, but back then, there were no schools that exclusively taught how to create manga. That’s why I decided to study graphic design, instead, but I knew my heart was in a different place, I just couldn’t muster up the courage to tell my parents that I wanted to pursue a career in fine art.That’s how I ended up working for Hakuhodo after graduating.

Manga Artist Osamu Tezuka author of Astroboy

最初は漫画家になりたかったんですよ。手塚治虫さんが大好きで漫画の事しか考えてなかったんだけども、僕の父親の友達に漫画家がいて。その当時人気があった原一司さんっていって、その人に絵を見てもらってたんだけども、結核で亡くなっちゃうんですよ。「どうしようかなあ」って思ってるうちに美術学校に入って続けようと武蔵野美術大学に入ったんだけども、今と違って漫画科なんてなかったからグラフィック・デザイン科に入ったんですよ。それでデザインの勉強をして、本当はこっちの方には行きたくなかったんだけども、親の希望を裏切って実は画家志望という事を言えなかったんで、そのまま卒業して博報堂に入ったという事なんだよね。

Being alive during a tumultuous time like WWII, where air raids destroyed half of Tokyo, have these sorts of events influenced your decision to become an artist or affected you in any way as a child?

過去のインタビューでも仰られてると思うんですけど、第二次正解大戦中の厳しい環境、特に空襲を幼少期に経験されて、田名網さんの人生観や人間性にどの様な影響を与えましたか?

Shot by Tsubasa Saitoh

I always get asked this question, but in essence, experiencing war as young as I was back then, has made some of the most intense memories I’ve had in my entire life. It was so intense, all the other memories from that period in my life just perished.

I remember coming out of the bunker after the air raids, and there were piles of bodies all over the roads. Not a lot of people have to go through this as a child, but because I did, anything that has to do with war triggers flashbacks to those horrid days. Piles of bodies on roads and sidewalks. I saw unspeakable things that are so horrific, it still haunts me when I work on my pieces.

いつもそういう話をしてるんだけど、要するに僕の過去の記憶の中で一番強烈なものっていうのは、幼児期に経験した戦争中の空襲ですよね。その記憶があまりにも強烈で、それ以外の事が消し飛んじゃうぐらいの戦争体験だったんですよね。僕が空襲で防空壕に母親と一緒に避難して出てくると、道路に空爆の跡と死体の山があるのよね。本当に幼い子供の頃にそういう経験をする事は滅多にないじゃないですか。だから今も戦争絡みのメディアなんかを見るとまざまざとその頃を思い出すのよ。本当に死体が道路に、歩いていく道にも、いくつも転がってたわけですよ。そういう恐怖っていうのは筆舌に尽くしがたい様なものなんですね。その時の恐怖体験っていうのは、あまりにも強烈なために現在でも物を作ったりする時に、そういうイメージだったり考えが絶えず蘇るわけ。

One of the Sabukaru team’s grandmother’s is about your age, but she was in Hokkaido, so she didn’t have much memory of experiencing the air raids. Location must’ve had to do with what you experienced?

メンバーの一員の祖母も田名網さんと同い年ぐらいなんですけど、北海道出身のようで空襲の記憶の話をあまりされなかったそうです。やはり場所によって戦争の実感がかわってくるものですよね。

Precisely. My family and I lived in Meguro, Tokyo, and Meguro was one of the worst places to be during that time. The Americans flew the B-29 bombers over Tokyo right around dusk, and it’s hard to imagine now, but hundreds of planes covered the sky like a carpet and dropped hundreds of bombs. From people to homes and buildings, everything was devastated by the carpet bombing. It’s an experience like no other, and it’s been impossible to forget about even after all these years.

そうそう。僕は目黒に住んでたんだけど、目黒は空襲が激しい所だったのよ。それでいわゆるアメリカの B-29 っていう爆撃機が、今では想像もできないんだけど、絨毯爆撃っていうのを夕方やって。絨毯爆撃っていうのは50機ぐらいの飛行機が隣り合わせにくっついて、絨毯の様な形で爆弾を落とすんだけど、爆撃された所は全滅するわけよね。だってそれだけの飛行機が集団で爆撃するんだから、そのエリアの人は全員死亡するわけじゃない。そういった様な経験をしてるから、ちょっとやそっとじゃ自分の脳裏から消えない。

The trauma remains to this day, doesn’t it?

ある種トラウマの様なものですよね。

Therapy was not a thing, because we had no therapists around back then but there really should've been. I managed to be as old as I am today, but the vivid flashbacks happen recurrently to this day.

Keiichi Tanaami in his studio, 1968

僕の時はなかったけど、本当はリハビリとかしなきゃ駄目だったんだけど、その頃そんなものをしてくれる人なんかいなかったから。それでそのまま大人になっちゃったわけだけど、一種の後遺症として未だに残ってるんだと思うのね。

You’ve mentioned how hallucinations you had overcoming an illness have inspired some of your works. Is art a coping mechanism to overcome these difficult experiences or a way to get in touch with your subconscious?

結核を患って療養中に体験した幻覚が作品のインスピレーションになっている事を伺っているんですか、やはり作品の制作を通してこれまで経験された困難やトラウマを対処、又は潜在意識の詮索している様に感じますか?

Shot by Tsubasa Saitoh

Tuberculosis doesn’t require a lot of treatment, and it’s actually a lot more of recuperation. So, after taking my medication in the morning, I often aimlessly walked around the hospital. The ones I took in the evening on the other hand, were much stronger, so I often burnt up with fever for several hours after. That’s when the hallucinations started, and I can’t tell if I was actually hallucinating or having a nightmare, but the images were vivid.

There’s this famous painting by Salvador Dali, and the same picture appeared every single night. The reason is quite simple, and it’s because someone brought me Dali’s art book when they visited, and I often flipped through it in the afternoon, so the same images I saw came back to haunt me in the evening.

Salvador Dali’s “The Persistence of Memory”

The other thing is, I stayed in the Japanese Red Cross Medical Center near Roppongi, and there was this humongous tree right outside my window. Roppongi used to be famous for having humongous trees around, and the pine tree outside my window was probably one of the more famous trees, but in the evening, the same tree started distorting like Dali’s “The Persistence of Memory [1931]”.

Everything was wonky in the evening, but as soon as the sun rose, everything was back to normal, and I thought that was interesting, so I decided to record everything I saw. By no means were they good days, but putting my experience down on paper released me from some of the pain. After being discharged, I decided to make them into pieces, and it was one way of coping with the trauma.

結核って療養が凄く長いんだけど、治療っていうものがあまりないのよね。だから注射だけ打った後は病院内をぶらぶらしてるわけよ。だけど夜になると注射も凄く強くなるんだけど、その後数時間は凄い発熱するわけよ。それで発熱をしている時に病院の白い壁に、幻覚なのか熱でうなされているのかわかんないんだけど、映像が映るわけね。それがダリの「ポリトルヤードの入り江」[13:19] っていう有名な絵があるんだけど、それが毎日決まってそっくり映るのよね。何故かというと昼間お見舞いに来てくれた人に「退屈だ」っていったら、ダリの画集を持ってきてくれたのよ。それをきっと昼間に見てて、その映像が夜うなされて壁に映るんだと思うんだけど、連日の様に映るのよ。

Shot by Tsubasa Saitoh

そういった経験と、日赤病院っていう所で入院してたんだけど、僕のいた部屋の窓に巨大な松の木があったんですよ。六本木の近くの病院なんだけど、六本木っていうのは六本の有名な巨木があるので付けられた名前らしいんだけど、その中の一本が日赤の庭にある。だからその松の木がダリの「記憶の固執(1931)」みたいに、高熱でうなされてるからニューンと歪曲して見えるわけよ。そういう色んな映像が見えたり、松の木が曲がったり、毎夜の如く出てくるわね。それで結局昼間は平熱になるからパッと治っちゃうんですけど、これは面白いと思って記録しておこうと思って毎日の様に描いたわけ。それでそういった諸々の恐ろしいというか面白い記録を退院してから作品にしたわけ。だからそういった入院中の記録とそれに類似した色んな事を記録してた事によって自分の苦痛から解放されるわけよ、作品化する事によって。それで退院してから入院中の記憶を作品化して苦い経験から逃れたわけですよ。

The sketches you drew during your hospitalization ended up inspiring your personal style?

入院中に見た事を絵にする作業が後にスタイルを変えるキッカケとなったという事ですか?

Photo credit @keiichitanaami_official

Exactly. I ended up sketching a ton, so I referred to these sketches to create new pieces. Like I said, it was one way to relieve some of the pain I felt at the time.

そうそう。それが物凄い数のスケッチになったので、それを基に作品を作った。それで作った事によって病院で描いてた自分自身の苦痛からも若干解放された。

Other than your wartime memories, are there any other crucial moments from your childhood that influenced your career as an artist?

戦時中の記憶が主にアーティストとして活動するキッカケになったという話をしてくれたと思うんですけど、戦争体験以外で他に大きなキッカケとなる青春時代のエピソードってあったりしますか?

My father’s younger brother, so someone I called uncle, was a little bit weird back then. He was what we call an otaku today, and he unfortunately died during the war, but he used to collect a lot of things since his college days in Keiō University. Back then, Japan, Germany, and Italy were in a Tripartite Pact, so a lot of pictures and postcards with Hitler and Mussolini had come into Japan, and my uncle had a huge collection of them. There also used to be this film magazine called “Star” back then, and it had a lot of colored pictures of the newest Western movies coming out, which my uncle had collected, as well.

Photo credit @keiichitanaami_official

My grandma always told me not to mess with his collection because she thought he was coming back, but when she went out of the house to run some errands, I snuck in his closet to check it out. It was exciting digging through his collection, and he had boxes full of postcards to collages of film stars and posters, and I used to play around just rearranging them. I much preferred checking my uncle’s collection out rather than playing outside as a kid, and I only realized much later on that his collection was a huge factor in why I love collage work so much. I received my uncle’s things when I got much older, and I decided to create a lot of collages from his collection.

Photo credit @keiichitanaami_official

僕の父親の弟、だから叔父さんなんだけど、当時としては変わった叔父さんで。今でいうオタクな叔父さんで、戦争に行って亡くなっちゃうんだけど、それまで慶応義塾大学に通ってた頃から色々コレクションをしてて。その頃日本とドイツとイタリアは日独伊三国同盟っていうのがあって、ヒトラーとかムソリーニの写真の絵葉書が流入してたんだけど、叔父さんはそれの膨大な数のコレクションをしてて。それから日本の映画雑誌で「スター」っていうのがあって、こんな大きくて結構立派な本だったんだけど、そこにはその当時の色んな洋画の写真をカラーで扱ってて、そのコレクションも山積みになってたわけ。

Photo credit @keiichitanaami_official

それでうちのおばあさんに叔父さんが戦争から帰ってくるからいじっちゃいけないっていつも言われてたんだけど、おばあちゃんが何処かに出かけてるすきに、叔父さんのコレクションが入ってる納戸に入って本とか絵葉書を見るのが楽しみだったわけですよ。その中に絵葉書だけじゃなくて、叔父さんが切り抜きしたスターの写真とかがいっぱい箱に入ってたわけ。それがまた子供ながら凄い面白くて、色々並べたりして遊んでたんだけど、その時の経験っていうのは後年の僕のコラージュ・ワークに凄く影響を与えたんじゃないかなあって思うのね。それから後年、叔父さんの遺品が大人になった僕の所に全部来たわけですよ。それから叔父さんが残していった膨大な数の写真とかを使ってコラージュ作品をいっぱい作ったわけですよ。

How old were you when you first saw your uncle’s collection?

叔父さんのコレクションを初めて見たのは何歳ぐらいでした?

Shot by Tsubasa Saitoh

I was about 4~5 years old. I did play outside as a child, but I was a little bit weird, and I developed this fascination for unconventional things. That’s probably why I ended up where I am today.

四〜五歳。子供の遊びも他にあったんだけど、僕はその時からちょっと変わった子で、そういうものに異常な興味を持ったのね。それがきっとこういう方向に進むキッカケになったんだと思う。

Shot by Tsubasa Saitoh

Being born and raised in Meguro, Tokyo, it’s safe to say that Tokyo is part of your identity. What are some of your favorite places to go in the city when you want to clear your head?

地元の目黒で過ごされた数々の記憶が田名網さんのアイデンティティーの一部として生きてると思うんですが、制作中に煮詰まった時にリフレッシュをしに行く場所、又は単純にお気に入りのスポットってあったりしますか?

Second hand bookstores in Kanda, a neighborhood known for vintage books

I don’t really go anywhere to clear my mind because I love what I do. But I do love going to bookstores, and I often visit Daikanyama to look for books. Kanda is also somewhere I go to check second hand bookstores.

自分の好きな事が仕事になっちゃってるから、あんまり色んな所に行ったりしない。でも唯一行って楽しいのは本屋さんぐらいしかないのね。だから代官山のニチタイサン [22:13] はしょっちゅう行くんだけど、そういうのが息抜きというか。本屋さんが好きなんだよね。それから神田の古本屋さんなんかもよく行くのよ。

T-Site [Tsutaya Books] in Daikanyama

You've mentioned how manga and movies are big influences for you, and it’s evident from how you include imagery of Micky Mouse and Marilyn Monroe in some of your works. Are there any particular influences that you can point to being impactful that you discovered well into your early adulthood?

田名網さんの作風を見る限り、漫画や映画の影響が大きい事がよくわかるんですが、幼少期以降、田名網さんが青年の頃に特に影響されたものってあったりしますか?

Shot by Tsubasa Saitoh

When I was in junior high, I used to go to this movie theater in Meguro, and they were famous for screening B-movies. Japan lost the war, so the U.S. used to import a lot of their propaganda films to show how great of a country they were. A lot of the movies showed how lavish their lifestyle was, and most of the films were made to show the Americans to be the hero. Every single film they showed a form of praise, and I had nothing else to do to pass the time, so I went to the theater to watch a couple of hundred of those films a year.

Photo credit @keiichitanaami_official

I learned a lot about Western culture, from how they lived to all the movie stars, but they also screened short movies like Disney’s “Steamboat Willie [1929]” in between the feature length films. I came across Betty Boop for the first time in the theater, and you can watch these short movies over and over again if you come in for the whole day. I enjoyed watching these short movies so much, I started to come to watch them instead of the actual films.

Shot by Tsubasa Saitoh

So, the reason I apply comical elements to my work isn’t just because I like them, but also because it left such an impact on me as I was growing up. The Mickey Mouse I knew wasn’t so round and cute, but the rather rugged characteristics of these characters imprinted themselves in my core memory. It wouldn’t be an understatement that the inception of manga and anime was found in these kinds of theater, but even if it weren’t the comical elements I saw back then are still well and alive in my works.

Photo credit @keiichitanaami_official

僕が中学生ぐらいの時は目黒に住んでて、権之助坂っていうのがあるんだけど、その坂の途中に小さい映画館があったの。いわゆる B級映画を専門館で、その頃は敗戦国だから、アメリカの映画を輸入するんだけど、好きなものを選べないじゃない?要するにプロパガンダなんで、アメリカが如何に素晴らしいかっていうフィルムしか輸入できなかったのよ。だからアメリカの凄い豪華な生活シーンが出てくる映画だとか、アメリカを英雄に仕立て上げるものだったり、それから戦争映画でもアメリカが一方的に勝つ様なストーリーばっかりだったの。アメリカ礼賛ものばかりで、当時は映画の他に娯楽もなかったから年間~百本もずっと見てたわけですね。

Shot by Tsubasa Saitoh

Shot by Tsubasa Saitoh

だから僕の作品の中にコミックスとかそういうものの応用をしてるんだけど、単に好きだからってだけじゃなくて、僕の子供時代の記憶の中で強烈に刷り込まれてわけよ、ミッキーとかベティーが。今のディズニーランドのミッキーじゃなくて、昔のもっと無骨な、あまりかわいくないミッキーなんだけど、そういうものの形状も含めて僕の中に刷り込まれちゃってる。そういうものを僕は映画館の中で見てたから、その時の記憶っていうのが漫画の原点で、その映画の中にコミカルな要素っていうのがいっぱいでてくるんだけど、その時の感じが今になっても生きてるんだよね。

More so than the feature length films you saw in the movie theater, the short movies had a greater impact on your personal style?

当時映画館で見てた本編の映画よりその間に映されていた短編映画の方が今の作風の影響が大きいという事ですか?

Precisely. Japan lost the war, so there was very little to no entertainment outside of watching these films. After watching the same short film for about three times, I was able to remember it enough to start sketching them under the emergency light, and I used to go back home to color them in with crayons to show my friends in school. The short films by Disney are the reason I’m remotely interested in animation, and although I had no clue back then, the sketches I made of these films found its way into what I do nowadays.

Shot by Tsubasa Saitoh

そうそう。その頃は日本も敗戦国で絵本も何も売ってないわけですよ。それで考えたのは、一日三回ぐらい見ると、非常灯の下が少し明るくなってたから、そこで映画のコマをみんなを映したのよ。三回ぐらい見ると大体ショートフィルムの余白が描けるんですけど、家に帰ってクレヨンで着色をして、学校に持ってってみんなに見せたりした記憶がある。だから僕がアニメーション制作とかに興味を持ち始めたのも、その頃のディズニーのものを見て、模写して再現したものが生かされてるんだと思うのね。

Photo credit @keiichitanaami_official

You attended Musashino Art University in the 1960s during a very eventful period when there was surge of student protests in Japan. What was the scene like in college, and what were your thoughts when these protests were swooping Japan?

1960年代に武蔵野美術大学に在学されてた時に、学生運動の勃発などで日本の美術界も大変な時期だったと思うんですけど、その当時のアートシーンはどういうものでしたか?

University Student Protests Japan 1968

I actually don’t really remember my art school years that well because I didn’t really go to school [laughs]. I can count the days I stepped into campus, and I wasn’t really in the art scene back then. I went to study design when the educational system wasn’t really properly set up yet, and we used to have famous designers come in once a year, but they only ever showed their work and went home right after since they were so busy. There wasn’t much going on, to be honest.

Even if I did go to school, it didn’t make much sense for me to go on campus to learn since I got a lot more done studying on my own. I was classmates with people like Genpei Akasegawa and Shusaku Arakawa, but all the people who made a name for themselves never attended classes, either, and I saw them more times outside of campus doing their own thing.

なんかねえ、あんまり学校も行かなかったし、美術学校の思い出ってないんだよね。ほとんど行ってないから[笑]。本当に学校に行ったっていう記憶は数える程しかないし、まだアートシーンに目を向けられるところにも行ってなかった。僕の時代のデザイン科を卒業してる子って、教育のシステム自体がまだ完成してなかったし、年に一回ぐらい著名なデザイナーを招いて講演とかしてもらったんだけど、そういうデザイナーも忙しかったから、来てもらって作品を30秒ぐらい見せてもらって帰ってったの。

その程度のもので、学校に行っても勉強になんなかったのよ。だから自分でやろうと思って。僕の同級生とかに赤瀬川原平とか荒川修作みたいな今も有名なアーティストがいっぱいいるんだけど、その連中も学校では会わなかったけど、どっか他の場所で会ってた。だからみんなほとんど学校に行ってなかったと思う。

So you weren’t in any way involved in the student protests that were happening back then?

当時行われてた学生運動などにもほとんど関わりなく卒業されたという事ですか?

Not at all. I don’t really have a lot of good memories from my college years.

そうそう。だから美術学校の時はあまり良い思い出がないね。

As a young artist, you probably encountered a lot of different artists from the 1960s~1970s, there was aN AVANT-GARDE collective called the “Neo-Dada Organizers” active in Shinjuku. Did you MEET UP OR COLLABORATE WITH THEM?

「ネオ・ダダイズム・オルガナイザーズ」ではアートとレイヴの境界線を破る様な活動をされてたと聞いているんですが、田名網さんが卒業してから活動が盛んだったと聞いています。このグループについてお話をお聞かせください。

Yoshimura Masanobu advertises Neo Dada Exhibition [Tokyo, 1961]

Back then, one of the members, Yoshimura, had an atelier in Hyakunin-cho, Shinjuku, and it was in one of the first buildings Arata Isozaki designed. The building itself still exists, but nowadays it’s a gallery space for Chim↑Pom. We didn’t have a lot going on in our lives, so the Neo-Dada members used to come in and out of Hyakunin-cho, drinking and hanging out.

Neo Dada Organizers mid performance [Tokyo, 1960]

I was pretty good friends with the famous Butoh dancer Tatsumi Hijikata and the artist Ushio Shinohara back then, but before Hijikata became a world famous dancer, he used to be a classic ballet dancer for the Ando Mitsuko company; a traditional modern ballet company where all the dancers were slender, tall, and beautiful. Hijikata on the other hand, since his family’s originally from the Tohoku region, had short crab legs, average looking face, and was built like a farmer. He stuck out like a sore thumb, so he was sort of baggage for the ballet company.

Tatsumi Hijikata

He never really got the chance to get on stage to dance, so Shinohara, whom I called Gyu-chan, told him that he should just do his own thing. He actually took it seriously and thought about it hard, but Gyu-chan teased him and suggested that he should strangle a chicken on stage. To everyone’s surprise, Hijikata took it seriously, and actually went on to do exactly that, and someone from the ballet company heard about it. Unsurprisingly he got fired immediately.

Ushio Shinohara [Gyu-chan]

I didn’t hear a word from him for a while, but after some time, I got an invitation for his first show. What was amazing about his show was that his very own style, which would be known as Ankoku Butoh later on, was something that completely disregarded the idea of traditional Butoh, and it was a huge hit around the country.

It was about exposing the ugliness of human nature, so the costumes were dirty and rugged as if they were dragged through mud, and the performance itself saw him crawling and squirming on the floor. Everything and anything about traditional Butoh was challenged in his performance, and it created an entirely new genre. People loved it, and he achieved success through that.

Tatsumi Hijikata Butoh Performance

Having watched him so close, it was amazing, but it also taught me an important lesson. I was still quite young, and his path to success was unconventional, so it inspired me in a way I’ve never experienced before. Not only did he in denial of his own body, but from his character to his own entire life, Hijikata found a way to create something from completely rejecting his entire self. It was a pleasure watching that very close, and very lesson I learned from him helped him in my life later on.

その頃は新宿の百人町っていう所でネオ・ダダのメンバーの吉村君っていう人のアトリエがあったんですよ。そのアトリエは磯崎新さんが初めて設計した個人住宅の中にあって、個人住宅は未だにあるんだけど、今は Chim↑Pom が買い取ってギャラリーにしてるの。その当時みんな暇だったから毎日の様にメンバーで集まって酒盛りして遊ぶ場だったんだけど、百人町に色んな人が出入りしてたのね。

Neo Dada [Tokyo, 1960]

僕はその頃舞踏家の土方巽とメンバーの篠原有司男と仲良くて、よく遊んでたんです。ただ土方っていうのは今は凄く有名な舞踏家になっちゃったけど、その頃はアンドウミツコっていうクラシックバレエ団にいたのね。そこはいわゆる伝統的なモダンバレエのスタジオなんですよ。だから女性も男性も足が長くて顔が良いダンサーばっかりだったんですよ。ところが土方っていうのは足が蟹股で、東北の生まれだから足が短くてお百姓さんみたいな体してたのね。それで顔もそれほどのものではないから、結局バレエ団でも容姿端麗じゃないからお荷物になってるわけよ。舞台も抜擢されないから、僕の友達の篠原有司男、ギュウちゃんっていうんだけど、彼が土方に「こんな事してても駄目だから、自分で舞台を講演しろ」って言って、内容をどうしようと迷ってた土方に「鶏の首でも締めてろ」って返したんだけど、土方が面白いと思ったのか舞台でやったのよ。それでバレエ団の人がそれを聞いてアンドウから速攻クビになっちゃったわけ。

Tatsumi Hijikata

それからしばらく会わなかったんだけど、ある日土方から舞踏の講演の案内状が来たのよ。それで見に行ってびっくりしたんだけど、結局暗黒舞踏っていう今までの舞踏の概念を全く否定した新たなスタイルを土方が作り出して、それを土方が講演をして回って大評判だったんだよ。結局肉体の醜さをそのまま晒す様に、人間の不格好さを舞踏の中に取り込んで、それを踊りとして見せたわけ。それでコスチュームもバレエ・ダンサー起用の綺麗なものじゃなくて泥を塗った汚い恰好で、地べたに這いつくばって、それを舞踏と称してショーをやってたわけなんだけど、それが世界的に大評判になって。結局今までの舞踏の良しとする部分を全て否定して新たな舞踏の世界を組み立てたわけでしょ。それで彼は大成功したわけね。

Ushio Shinohara [Gyu-chan] a close friend of Keiichi Tanaaami

僕はそれを間近で見てて「こういう生き方もあるんだなあ」って、まだ若かったから凄く影響を受けたというか勉強になったね。自分自身の人生、人格、身体と、あらゆるものを否定して新たなものを仕立てるっていう作り方もある事をそこで僕は知ったわけ。その当時間近で見る事によって凄くいい勉強になったし、その後の人生で凄く訳にたったのね。

Tatsumi Hijikata mid Butoh performance

There are a lot of recurring symbols in your work, and goldfish can be found quite often. Is there a particular meaning behind your use of goldfish imagery?

田名網さんの数々の作品を通して登場する金魚の絵についてなんですが、これは何かを象徴してたりしますか?

Not only the goldfish, but everything that appears in my work has a meaning. I find that explaining everything would take away from the painting., so I refrain from giving the meaning behind them. But if I must give you some examples, the recurring image of the human-like spider is a symbol for when I had to evacuate to Niigata prefecture. I got intestinal catarrh, and I was in bed for quite a while, but I’ve actually never been to a rural area like Niigata, and I was quite surprised to see spiders as big as sparrows. There was a huge webb on the window, and I once saw a grown sparrow being caught in it. The spider ate it in seconds, and for someone who grew up in the city it was terrifying imagery.

Photo credit @keiichitanaami_official

There are a lot of things that have shocking anecdotes in my paintings, and the goldfish is another one of those. My grandpa used to breed expensive goldfish breeds like Ranchus and Telescopes, and we used to have a huge fish tank just beyond our garden. I used to study and eat snacks in front of the garden, and when I went to check out the fish tank, the goldfishes used to scramble toward me thinking I had food on me. It was quite fun screwing around with them, but once the air raids started, we hid in the bunker we dug in our garden, just under the fish tank. The air raids happened during the evening, and the bombers used to fire flares before dropping the bombs as to guide them, so the sky turned bright orange as if it was in the afternoon.

Photo credit @keiichitanaami_official

The flares itself were a peculiar sight, but I used to look up to the fish tank, and the bright orange color used to reflect off of the scales of the goldfish, creating this sparkling effect. It wouldn’t have been so noticeable if they were regular goldfishes, but these were huge breeds, so they sparkled so beautifully. The air raids scared me to death, but secretly, I was also excited to see the sparkle that only happened when the flares dropped.

The same scenery appears in some of my works, and they’re afterimages of the war. Each and every image I put in my paintings have an episode I’ve personally experienced, but I don’t ever explain them to people because I don’t want them to see my work developing a framework. I get asked a lot of questions when I do shows in the U.S., but I never really go on to explain them since it would take the fun out of my paintings.

Photo credit @keiichitanaami_official

金魚に限らず一つ一つに意味があるんだけど、それを説明しちゃうと絵がつまんなくなっちゃうのよ。「これはこうです」って言っちゃうとつまんなくなっちゅうから説明してないんだけど、例えば人間の様な蜘蛛っていうのもよく僕の作品の中にでてくるんだけども、それは戦時中に空襲から逃れるために新潟に疎開してたんだけど、そこで大腸カタルっていう病気にかかって寝込んでたの。それで窓の方を見てると、新潟の方って凄くて、蜘蛛もスズメぐらい大きいのよ。その巨大蜘蛛が窓いっぱいに巣を貼って、恐ろしい事にそこにスズメが引っ掛かるのよ。それでそのスズメを蜘蛛が一瞬にして食べちゃうんだけど、元々都会で育った僕からしたら想像もできない世界じゃん。

Ushio Shinohara [Gyu-chan] - Photo credit @keiichitanaami_official

そういったショッキングなビジュアルを見たエピソードが僕の絵の中に点在してるんだけど、金魚なんかの場合は僕のおじいさんがらんちゅうとか出目金みたいな高級な金魚の養殖をしてたわけ。家の庭先に畳二畳ぐらいの大きな水槽があったんだけど、その中に巨大金魚をおじいさんが飼ってたわけ。僕はその前で勉強したり、おやつを食べたりしてて、僕が水槽に近づくと餌がもらえると思ってガーって寄ってくるんだけど、そうやって遊んでたの。それから戦争が始まって空襲が始まるんだけど、水槽がある庭に防空壕を掘って、戦時中はその中に隠れてたわけ。その防空壕の中から水槽の方を見上げると、空襲って言うのは大体夜に来るものだったんだけど、いわゆる照明弾っていうのが落とされて辺り一面昼間みたいにオレンジ色に明るくなって。それを目掛けて爆弾が落とされるんだけど、その金魚の鱗に照明弾の光が反射してピカピカ輝くわけ。普通の金魚ならまだしも、巨大なものだから凄く綺麗に反射した光が輝くのよ。それを見てた僕は、戦争の恐怖っていうのは勿論あったんだけど、空襲の時しか見られないキラキラ輝く光が楽しみでもあったわけよ。

Photo credit @keiichitanaami_official

そういった経験が僕の今の絵の中にも出てくるんだけど、それは戦時中に見た巨大金魚の残像なのよね。こういう様に僕の作品の中に出てくる絵の一つ一つに僕の体験談から結び付けられる意味があるのよ。それぞれ説明できるんだけど、説明すると枠組みができちゃうでしょ。今仮に説明したけど、それぞれにストーリーがある。アメリカなんかで展覧会をするとしつこく意味を聞いてくる人がいるのよ。それを全部答えて説明してもいいんだけど、逆につまんないんじゃないかと思って。

A young Tanaami surrounded by his work photo credit @keiichitanaami_official

Your connection with 1960s counter culture runs pretty deep, especially with rock music. You collaborated with the legendary bands like Jefferson Airplane and The Monkees, but how did you end up designing these album covers for these bands? Were you originally a fan of their music, or did the partnership arise more spontaneously?

田名網さんの1960年代のカウンター・カルチャ―とのつながりに関る質問なんですけど、代表的な例でいうと Jefferson Airplane や The Monkees のレコードジャケットをデザインされていますね。この様なレジェンダリ―なバンドとはどの様な繋がりでコラボレーションされる事になったんですか?そもそもファンでこういった経緯で一緒にお仕事される事になったんですか?

Most of them are requests. I’m actually not a huge fan of these bands, so they were also requests, but I also get asked from friends and acquaintances too.

依頼されてやってるのが多いね。別に僕がファンとかではなくて、向こうから依頼が来るものなんだけど、後は知り合って頼まれる事もあって。

You've mentioned how Andy Warhol is a big influence, and you once flew to New York to find him. What about his work struck a chord with you, and did you ever end up crossing paths with people from The Factory?

過去にアンディ―・ウォーホルから大きな影響を受けたと伺っていますが、特に彼のどういったところから影響を受けましたか?又ニューヨークに行った際は The Factory との交流はありましたか?

I've met Warhol a couple of times, but the first time I met him, I was asked by NHK to direct the art direction for a special program on his first exhibition at the Daimaru department store in Tokyo station. We went into Warhol’s waiting room to film a short interview, but he was in a bad mood since he just arrived from the airport. We wanted to film Warhol facing the camera, but he was looking down the whole time, so I consulted his manager, but he asked us to come back some other time. The problem was that we only had that day to film since the deadline was coming up, so I decided to stop filming, and went on to create a collage of the animations I had made for the program, and submitted the one-hour long footage to the network.

I sent the video to Warhol after a while, and I was told that he absolutely loved it. The video still exists today, and the Mori Art Museum asked if they could use the footage for a Warhol exhibition they were doing a few years ago. Unfortunately, they couldn’t use it since they couldn’t get in contact with the composer of the music used in the video, and it’s a shame because I thought it would be pretty interesting to have shown it then.

ウォーホルとは何回か会った事あるんだけど、最初に会ったのは東京駅にある大丸百貨店で彼の展覧会を初めてやったのよね。その時に NHK が特別報道番組を作ってアートディレクターとして監督をしてくれないかって頼まれて。それで NHK のカメラマンと一緒に大丸の控室にウォーホルを尋ねたわけよ。ところが彼は来たばっかりで疲れ果てて不機嫌だったんだけど、ずっと下を向いてて。僕は彼の顔を使って映像を作りたかったんだけど、全然カメラの方に向いてくれなくて全然ダメだったのよ。それでアメリカ人のマネージャーに「今日はもう無理だから後日もう一度してくれない」っていうんだけど、NHK の方の締め切りが迫ってて、待てなかったのよ。それでしょうがなく撮影をやめてたんだけど、番組を作んなきゃいけないからそれまでこの番組の為に作ったアニメーションをコラージュして全編にちりばめて一時間の映像が完成したんだよね。

Andy Warhol

その後でウォーホルに映像を送ったんだけど、すごく喜んでくれたっていう事を教えてもらったんだけど、今でもその映像はあるんだけど、結構面白いんだよ。何年か前に森美術館でウォーホル展をやったんだけど、僕が作った映像を映したいって言われて許可したんだけど、映像に使ってた音楽の制作者の所在が不明だったらしくて。映すにしても著作が必要だったから結局駄目になっちゃったんだけど、本当はちょっと映したら面白かったんだろうなあと思ってる。

You have a very extensive body of work, but now that you’re in your 80s, what does a day in the life of Keiichi Tanaami look like these days? How do you maintain this creative productivity?

80台を超えても尚制作を続けられている事に関してなんですけど、最近のルーティンについて詳しくお話いただけますか?

Shot by Tsubasa Saitoh

It’s not exciting, at all, since my house is right in front of my studio, so I work hard until around sun down and go home after. I suppose I eat different things everyday, but my schedule is just a cycle of the same thing over and over again.

あんまり変化のない生活だから、仕事場の前の部屋が自宅なんだけど、とにかく仕事場で仕事を熟して、夕方には部屋に帰るっていう繰り返しのサイクルでやってる。何も面白味もない生活を送ってる。食べ物は色んなものを規制なく食べるんだけど、制作のサイクルだとか、スケジュールは本当にずっと同じ感じ。

Shot by Tsubasa Saitoh

You've previously mentioned how history’s master painters seldom felt tenacious about work from their last years, but now that you’re in your 80s, how do you keep your enthusiasm for creativity?

過去に「歴史上の画家や巨匠と言われる人たちは晩年の作品に執念を感じない」という様な事を仰られたと思うんですが、80台を超えても尚、創造への意欲をキープできてるのには何かの秘訣があったりするんですか?

Photo credit @keiichitanaami_official

Obviously, I feel my body doesn’t work like it used to before, but in terms of workload, I’ve actually never been busier. I felt the need to retire in my 70s, but now that I am in my 80s, things have surprisingly been working out. I’ve been getting a variety of requests, and I’m also exhibiting my work all around the world, so I have a lot more tasks to tend to, but so far I’ve been managing it pretty well.

肉体的には当然衰えを感じてるんだけど、仕事量に関しては若い頃より多いのよね。70台ぐらいになって駄目だなあと思ってたんだけど、今になっては意外と駄目になんないなあと思ってやってる。今の方が色んな注文が入ったり、展覧会なんかも世界中でやってるから、結構熟さなきゃいけない数がいっぱいあって。やらざるを得ないんだけど、それに応えられてるのが現状だからね。

What do you think is the key to artistic success, and how do you maintain your creativity?

アーティストとして成功する為の鍵、ある意味創造性を維持するための鍵ってなんだと思いますか?

I should be the one asking that question [laughs].

それは俺が聞きたいね[笑]。それはわかんないよ。

Are there any Japanese artists from the newer generations that you’ve mentored? Do you admire any of the new artists and their works?

若い世代で田名網さんが指導しているアーティストはいたりしますか?又最近面白いと思えるアーティストは居たりしますか?

Kyoto University of the Arts

I used to teach at Kyoto University of the Arts, and I remember Ataru Sato being a very interesting individual.

僕は京都造形芸術大学で教えてたんだけど、その時の教え子に佐藤允君って子がいて。その子は凄く面白いのよ。

What do you have to say to young kids who may want to be an artist?

最後にこれからを背負うアーティストに一言アドバイスをお願いします。

Shot by Tsubasa Saitoh

I used to teach at schools, but I can never seem to come up with advice to give. The only thing I ever tell my students is to work hard, but I don’t know if that’s considered as advice. Having taught a lot of kids in my lifetime, I’ve come to realize that being an artist isn’t something that can be taught. You’re constantly thinking on the job, and it’s not like certain skill sets are useful in overcoming hurdles. That’s why I don’t really give a lot of advice to my students, but rather have them absorb the things I say in our conversations.

Sato is another student of mine who I never actually took under my wing or anything like that, but he sort of observed how I dealt with life, and it looks like he’s doing quite alright. He took all the good things for him to absorb, and cut the things he didn’t like, and I’m under the impression that worked really well for him.

If you think about it, education is sort of a one way street, so I can only give my students thoughts from my perspective, but how are you supposed to understand that, especially in creative fields like art? It’s the same thing with giving criticism. How does it make sense for one teacher to judge and grade their work when the students are putting out ideas unique only to their perspective? I can never understand.

photo credit @keiichitanaami_official

僕は学校で教えてたんだけど、アドバイスって思いつかないんだよね。結局「一生懸命やりなさい」ってぐらいしか言えなくて。学校の先生をやってた時代も長いんだけど、やっぱりこういう仕事って教えられないなあと思うのよ。自分で考えないとどうしようもない仕事だから、教えてどうなるっていう問題じゃないんだよね。だから僕も色んな作家を育てたりしてきたけども、結局あんまり僕から言わないで、僕との会話の中で汲み取ってもらう方がいいと思ってて。

佐藤君なんかも僕が直接的に教えてないんだけども、なんとなく僕の生活態度とかを見て勉強してくれたという事だと思ってて、それがよかったのかなあと思ってるのよ。勝手に良いところは受け入れてもらって、悪いところは拒んでみたいな、それが良かったのかなあと思ってるのよ。教育って大体一方的な押し付けじゃないですか?「これやれ、あれやれ」ってそれはあくまで僕の主観で、押し付けられてる人にとってはわからないわけよね。だから批評って言うのも先生がよくする事なんだけど、教え子にとって良いと思って描いてるのに「駄目」って口に出して言っちゃうのは良くないと思ってるのよ。

What can you tell anyone who may have to choose between working on their passion or working for society’s expectation?

やりたい事を仕事にするのと社会に適応してやりたくない仕事に就く選択肢が迫られている人もいると思うんですが、これについて思う事はありますか?

shot by Tsubasa Saitoh

Well, what can they do except chasing their instincts? My mother used to hate the idea of me becoming a painter, because she came from a family of merchants.

She had two other sisters, and one of her sisters planned a trip to our home, but about an hour before they were supposed to come, my mother started cleaning around the house. I went to see what the ruckus was about, and I saw her flipping all my work inside out all over the house.

I asked her why she would do such a thing, and she simply said it was too embarrassing to show her sister. That’s the sort of environment I grew up in, but I still managed to become an artist. Although, I never got the chance to show any of my work to her because I never got the courage to.

Shot by Tsubasa Saitoh

やりたいんならしょうがないよねえ。僕なんかも母親が絵を仕事にしたいという気持ちに対して凄い拒否反応を起こしてたんだけど、やっぱり普通の商人の娘だからそういうものの理解っていうのが全くなくて。うちの母親は三姉妹で、うちに遊びに来たいって言いだして来る事になったんだけど、うちに着く予定の一時間ぐらい前にドタバタし始めて、何してるのかなあと思って見たら、部屋中にある僕の絵を全部見えない様に裏返してたのよ。それで「何してるの!?」って聞いたら「恥ずかしいから」って言ってね。そういう環境で育って、とにかく反対されてる意識があったから、自信を持って母親に作品を見せたり、もう亡くなっちゃったから生涯できなかったのね。

Words by Ora Margolis

Selected photos by Tsubasa Saitoh

Interview by Marta Espinosa, Ora Margolis, and Tsubasa Saitoh

Article layout by Sadaf Omari

![Akasegawa Genpei [1983]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57825361440243db4a4b7830/1671691666876-AXPMDVMVGAXMSCLC4H4E/%E5%85%AD%E6%9C%AC%E6%9C%A8%E6%8E%A2%E6%9F%BB004-1.jpg)

![Shusaku Arakawa [1980]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57825361440243db4a4b7830/1671691652915-GZ3GV57YBJO9VJUDGMXJ/eb74f85729127973a2e023d142465561-768x850.jpg)