The FRUiTS Magazine Phenomenon- Shoichi Aoki The inventor of The Street Snap

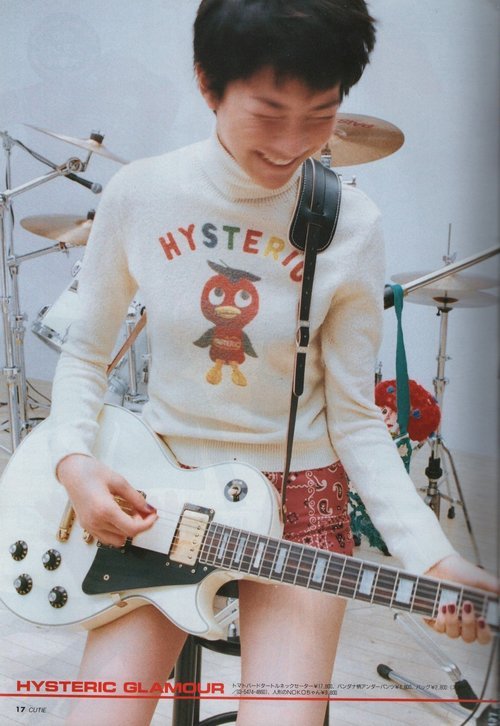

Shoichi Aoki, the founder of FRUiTS Magazine mid-shoot

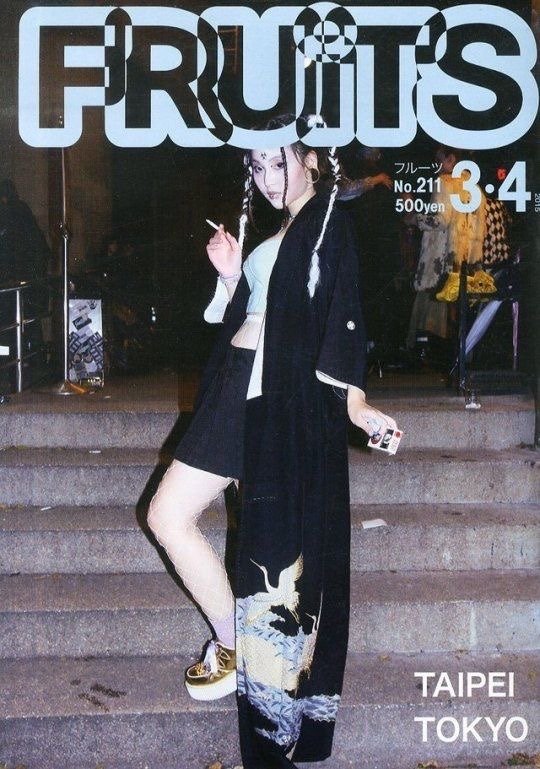

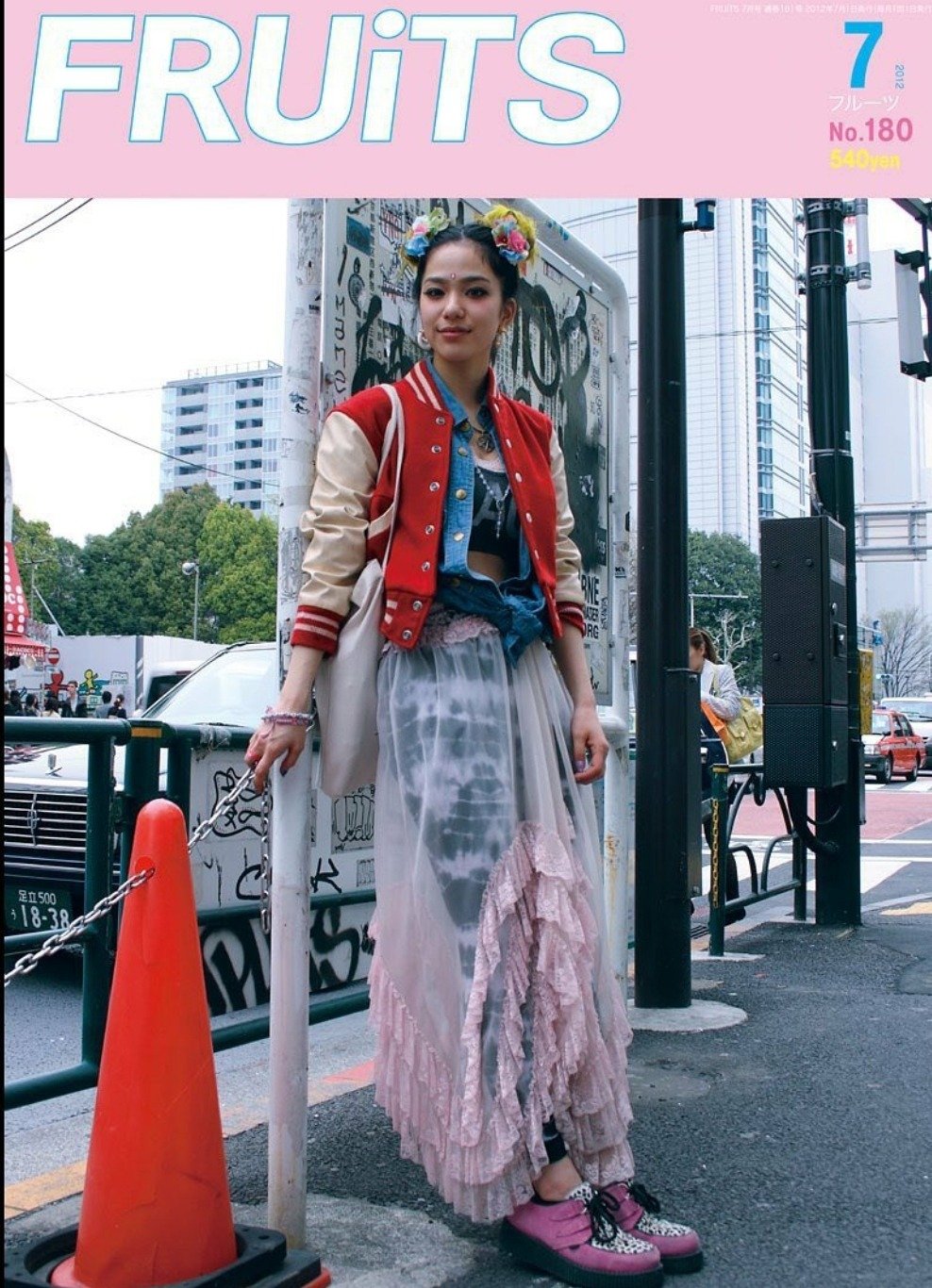

That’s what Shoichi Aoki Japan’s best-known street style photographer and founder of the “street style snap” genre proclaimed before publishing the final issue of his iconic magazine FRUiTs in 2017. The end of the magazine, seemed like a bad omen for the world of street fashion and ended it’s two-decade long and 233 volume long odyssey of capturing the best of Tokyo’s street style.

Yet, even after the last issue its legacy lives on. There’s a rumored a possible revamp in the near future [fingers crossed] after a 6 year long hiatus. Even if new issues on the horizon aren’t 100 percent confirmed, the good news is English language reissues of past versions have started to be printed since 2022.

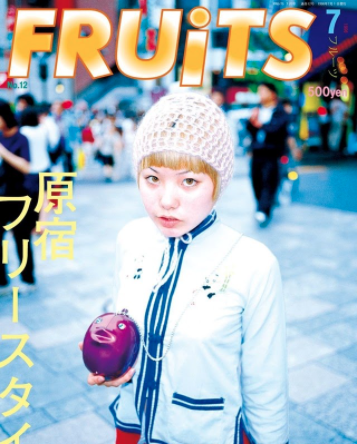

The English language version of FRUiTS’ first issue.

Why is FRUiTs still unforgettable, even years after its last issue?

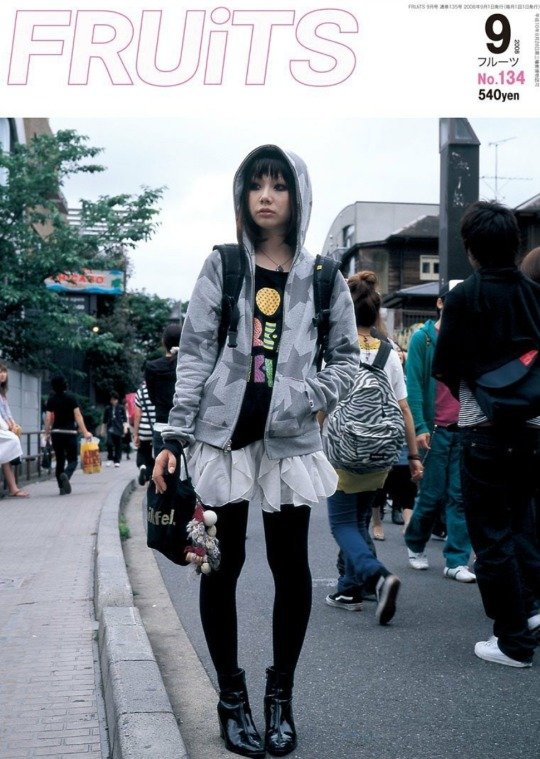

The magazine was the first and best-known street snap style magazine which influenced FASHIONSNAP.com and hoards of street style blogs that would come after; all of which can’t seem to match the original charm of FRUiTS’ pages paying long overdue respect to Tokyo’s style-conscious underground.

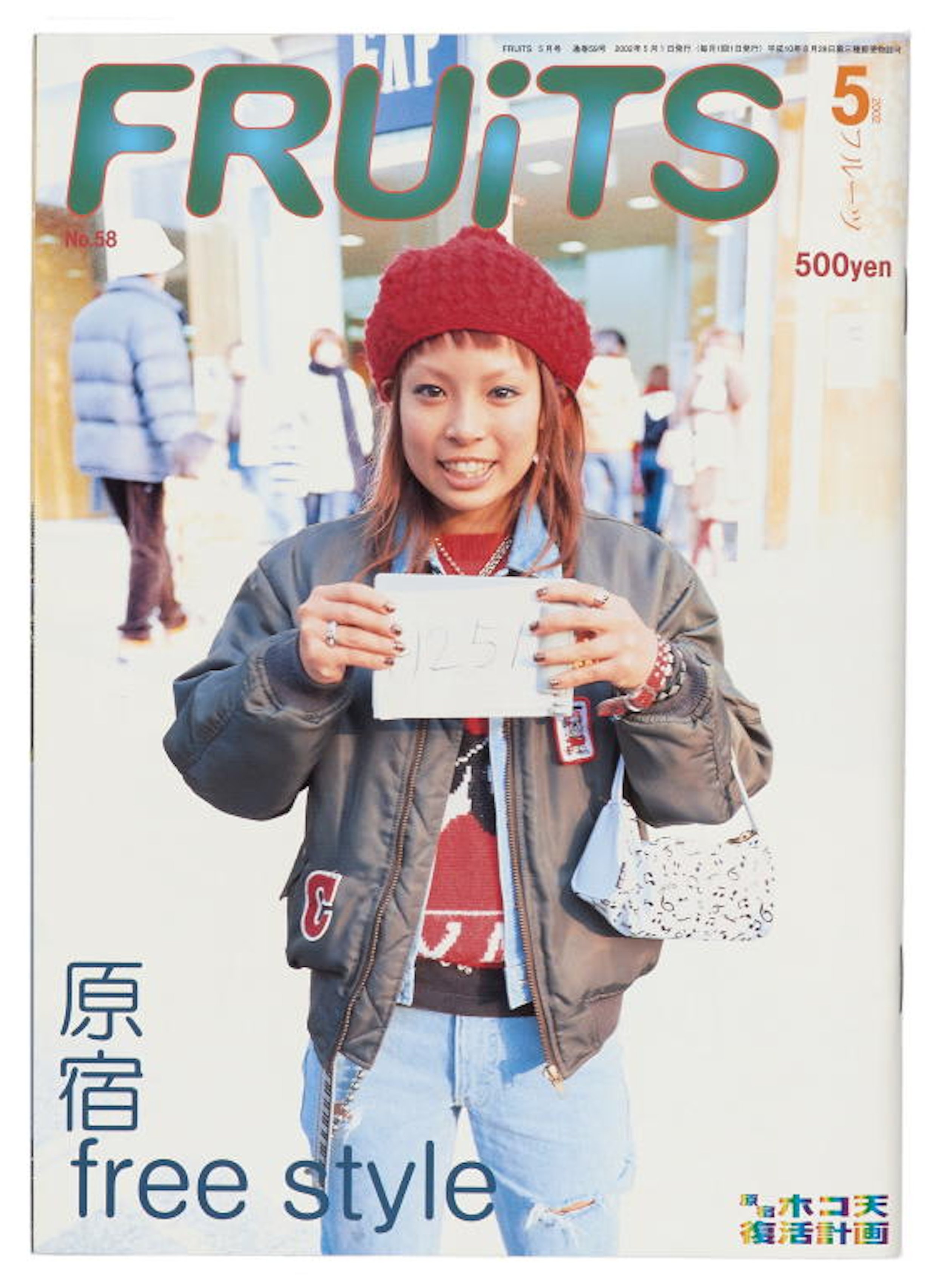

The concept of FRUiTS was simple: Aoki prowled the streets of Harajuku, identified a good fit, snapped candid photos of the person rocking it, and ended these guerilla-style photoshoots by asking participants a couple simple questions about personal style. Aoki’s “street snaps” come with a sense of surprise and urgency, befitting people who were suddenly asked to pose long before the advent of smartphones made being frequently photographed the norm.

This straightforward tactic unexpectedly sent shockwaves to the fashion world causing the “FRUiTs phenomenon” AKA the democratization of style. Because of FRUiTs, the fashion world increasingly turned to everyday people for fashion inspiration in the next decade.

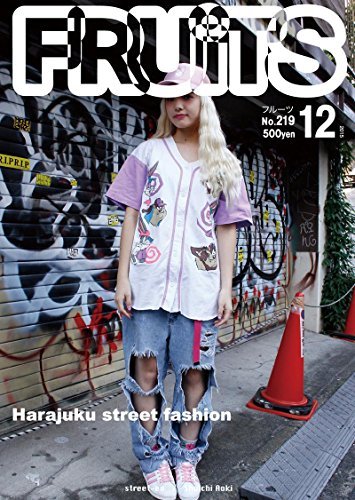

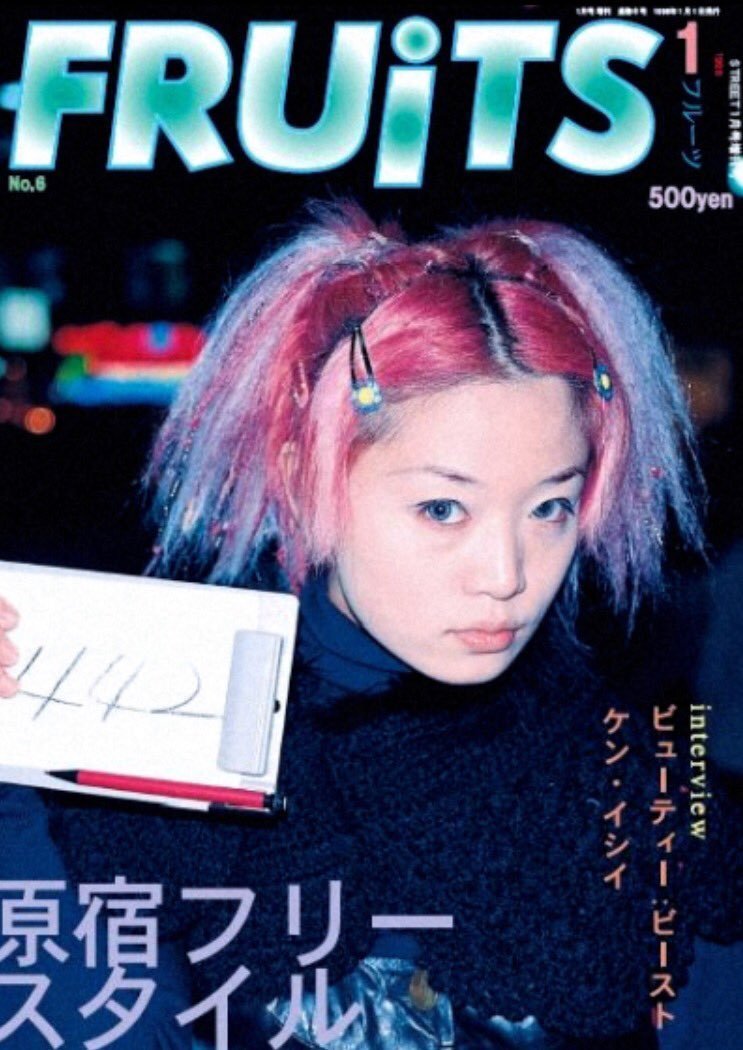

A couple of years after FRUiTs called it quits, there's been a widespread push from the new generation [born after its first issue was even released] dedicated to hunting down used copies at specialty bookshops or reading scans meticulously archived on Instagram pages galore by fans across the globe.

@fruits_magazine_archives one of the most popular Instagram pages dedicated to FRUiTS magazine scans.

Now calls for the magazine's comeback seem more urgent than ever, perhaps as a reaction to the rapid globalization of fast fashion brands [causing everyone to dress similarly with those same ubiquitous trendy pieces] or the plethora of sponsored social media posts promoting less than amazing looks by influencers- that leave us feeling a bit empty. Whatever the exact reason is, there’s a hunger for the return of the hyper-local character of trends and FRUiTs’ ethos of celebrating weirdness, individuality, and DIY flair. Let’s dive into how Shoichi Aoki and FRUiTs Magazine refined what “style” meant globally, and how Harajuku fashion made waves from Japan to beyond.

Pre-FRUiT’s era, much of fashion journalism/trend reports paid attention to the uber-rich, the runways, and the styles seen in multimillion-dollar advertisement campaigns, there were no well known magazines focusing on capturing what the non-ridiculously beautiful or well-connected were wearing.

Additionally, trends in Japan before the 90s often tried to mimic what was happening abroad in Europe or the U.S., with homegrown Japanese brands and trends being viewed as less cool than their foreign counterparts. However post- FRUiTs, around the early 00s the fashion industry became aware that the next fashion icon could be anyone from a loitering teen to a shop clerk on their way to work, and the West started to take fashion cues from the streets of Tokyo, as a step away from the eurocentricity that dominates fashion even today.

While most fashion magazines focus on perfection, unrealistic models, tasteful lighting, and clothing that costs more than the average person makes in a month, FRUiT’s did the contrary. The magazine celebrated the imperfect and the magic of reality in all its unretouched glory- with no planted “street snaps”, no insistence on featuring big brands, and a sense of beautiful awkwardness found only in the photographs of people unused to being the center of attention in it’s monthly and later bi-monthly issues.

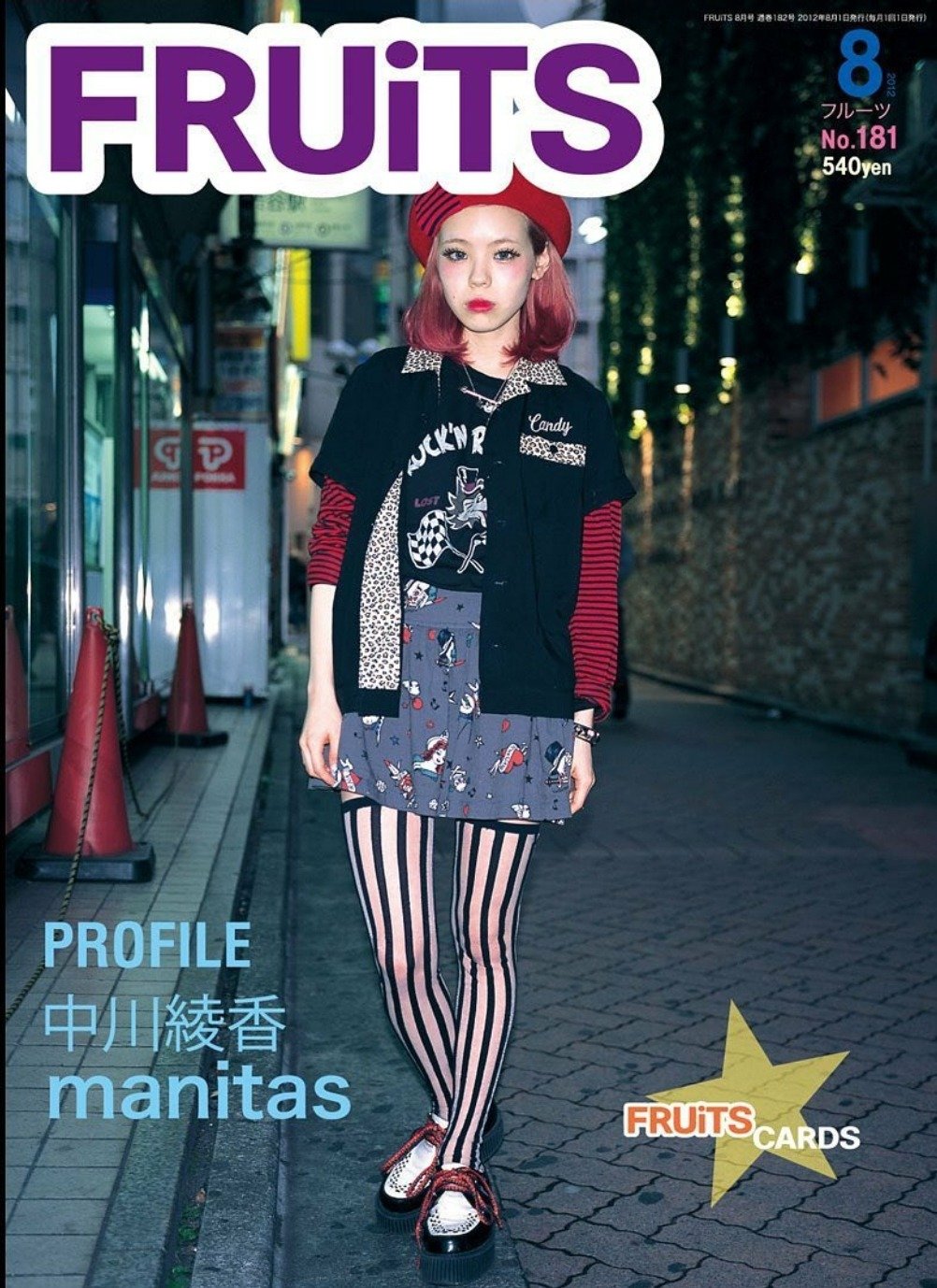

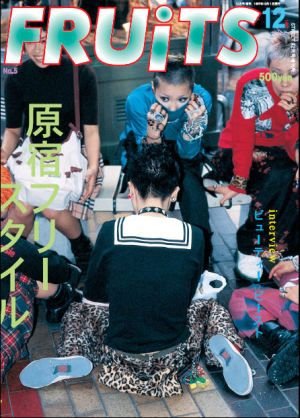

Aoki toyed with starting FRUiT’s magazine after starting another street snap magazine called STREET, except this time around he wanted to focus on the micro trends, the ups and downs, and the subtle shifts happening in Harajuku before it became the “Harajuku” of international street style renown. He recalls walking around the area [where he also coincidentally lived] in the 90s and feeling that something “big” was about to happen, chronicling the nascent seeds of looks later known as Japanese Gothic Lolita, decora, punk, visual kei, and the more subtle Urahara boy look.

Styles emerging during this golden age were often driven by a resistance to conformity and even the authority of what companies and large fashion brands determined stylish. Many FRUiT’s admirers championed smaller brands, second-hand clothing, or even customized garments themselves out of 100 yen DAISO trinkets or whatever else they could lay their hands on. FRUiT’s showcased a vision of style molded from the “bottom down” with starting the individual and what was seen on the street defining “cool”. FRUiT’s models may not have had money, clout, or traditional good looks but they did have “style”, something Aoki believed was an innate 6th sense of sorts, something known not learned.

Furthermore, the magazine sparked the phenomenon of Aoki-Machi [or a play on words of Shoichi Aoki’s last name and the Japanese word machi meaning “waiting”], street kids and style-conscious crowds loitering around the Harajuku area wearing their Sunday best–yes, “Harajuku Sunday” was really an activity in itself, all in the hopes of being snapped by Aoki. Through the creation of the concept of the “street snap” AKA a candid mini photoshoot of a person wearing an outfit that caught his eye, Aoki brought in another layer to subculture's development, the act of gathering in a specific area to see and be seen, by others in your subculture and the broader world- a chance to feel special if only for a day.

Since then, Aoki [who in addition to FRUiT’s and STREET has founded other style snap magazines TUNE and .RUBY] changed his outlook on there being “no more cool kids” to capture. Now he continues his mission using Instagram by documenting fashion's evolution one snapshot at a time in London, Paris, and of course Tokyo, with a continued optimism [thank goodness!] for what today’s street style has to offer.

Snaps from TUNE, another one of Shoichi’s ventures focusing on more subtle menswear based looks.

What killed Harajuku [temporarily at least]? From Aoki’s perspective, it was the rise of fast fashion retailers, people dressing more homogeneously, and a shift in the Japanese consumers' buying habits focusing more on the cheapness/quantity of their garments rather than quality. However, Aoki sees a brighter future ahead and finds a sense of pride in how today's trendsetters look to FRUiTs as a source of inspiration and a de facto style bible minus the commercialism of a traditional fashion magazine.

Sabukaru sat down with Shoichi Aoki talking about what makes a good outfit, how Harajuku became a style mecca, and if a FRUiT’s revamp is a possibility in the near future.

Can you please introduce yourself to the sabukaru network?

始めに自己紹介をお願いしてもよろしいですか?

I’m Shoichi Aoki, and I used to work on magazines like STREET, FRUiTS, and TUNE.

青木正一と言います。STREET とか FRUiTS 、それから TUNE を、今はどれも出してないんですけど、出してました。

Fashion and culture evolved pretty drastically since your teenage years during the 1970s. What made you decide to enter the fashion world as a photographer? Are there key memories you can point to?

青木さんがティーンエージャーだった1970年代頃とは大きくファッションやカルチャ―が大きく異なったと思うんですけど、ファッションや写真の方向に進もうと思ったキッカケやインスピレーションになったエピソードなどありますか?

It was early into the 1980s, right around when the DC boom* happened, when fashion was at the center of mainstream attention. I had gone to Europe just before, and I found fashion in Paris particularly interesting, precisely because it was different from how the Japanese dressed themselves. A few years later, I started to have this strong opinion about how fashion should be. Although fashion was dominated by the glitz and glam magazines and runway shows brought, I felt real fashion ought to be about what actual people wear on the streets. Having realized there wasn’t any media doing that, I decided I wanted to start one. This idea started around the mid-80s just before I turned 30 years old.

*The DC Boom (short for designers and characters) is a term for a transition within youth fashion and trends in Japan, where brands/styles originating from Japan such as Issey Miyake and Yohji Yamamoto became popular and respected, breaking previous cycles in Japan of only “foreign brands and looks” being the forefront of trendy fashion in Japan.

ファッションをやろうと思ったのは1980年代あたま頃で「何を仕事にしようかなあ」と思っていて、DC ブームの直前か丁度の頃ぐらいで、世の中的にはファッションが流行の中心だったりしてて。その前にヨーロッパをグルグル回ってた時があって、パリのファッションが面白い事をやってて「日本のファッションとは全然違うなあ」って感じた記憶がある。それから何年か経って、雑誌に載っている様なファッションじゃなくて人が実際に身に付けているファッションというのが本物のファッションなんじゃないかと思う様になって、そういうものを記録しているメディアがない事に気付いて「それを仕事にしていこうかなあ」って思ったのが1980年半ば、僕が30歳になる手前ぐらいかなあ。

You were taking street fashion snaps abroad for STREET magazine 10 years before starting FRUiTS magazine, what exactly made you decide to take snaps in Japan? Are there any particular episodes that you can point to?

外のストリート・スナップを撮ってた STREET 、丁度 FRUiTS を創める10年前にやってたと思うんですけど、海外の街中のファッションを撮ってた頃に国内のスナップを撮ろうと思い立ったのは何故ですか?キッカケとなるエピソードはあったりしますか?

Before FRUiTS, Japan didn’t really have fashion like that. I started taking street snaps just when the DC Boom happened in Japan, and it continued to thrive for the next 10 years, and Harajuku fashion as we know it today was born only after the end of the DC boom. I actually lived in Harajuku just around that time, and I noticed the first signs of the Harajuku style, thinking “this might be something special.” I thought of making a magazine out of this because not a lot of people noticed what was going on.

FRUiTS の前は日本でああいうファッションってなかったんですよ。それまでは DC ブームの初期ぐらいにストリートのスナップを始めて、それから10年ぐらい DC ブームが続いて、それが終わった頃に FRUiTS で取り扱っていたファッションが原宿で急にで生まれたんですよ。その頃原宿に住んでたので、それに気が付いて「これはひょっとしたらヨーロッパのファッションよりも面白いものが始まろうとしてるかも」と思って。まだ誰も気が付いてなさそうな感じだったので、ちょっと雑誌にしてみようかって始めた。

Other than the people you were taking photos of, what are some of the things you were consciously changing?

勿論被写体になった方々は変わっっていったと思うんですけど、意識的にスタイルをも変えようと思った結果が STREET から FRUiTS という形になったんですか?

I just thought Harajuku was really progressive, and I suppose Harajuku was always like that in a sense.

僕がその場所が一番オシャレだと思ったのと、原宿は原宿でああいう場所だったのかなあ。

What did your day-to-day life look like during your time at FRUiTS?

当時 FRUiTS を始めた頃の一日はどんな感じでしたか?

My day-to-day? We had just moved our office to Ebisu, so we came to Harajuku from there. We were only able to shoot during the day, so we were out until sunset. We went back to the office after, but that was basically our day-to-day. I was the one who edited all the photos, so I couldn’t go out and shoot every single day, but if I wasn’t editing, I was out in Harajuku taking photos of people.

一日ねえ。始めた時は事務所を恵比寿に引っ越して、そこから原宿に出てきて、日の明かりがある間しか撮らなかったので夕方まで写真を撮って事務所に帰るというのをほぼ毎日。編集も全部自分でしてたので毎日は撮れなかったんですけど、大体原宿にできるだけ毎日来てました。

How many snaps did you take each day?

スナップは一日何人ぐらい撮ってましたか?

We had to publish one magazine every month, so we took about 80 people each month. I suppose we were able to shoot 20 days out of the month, so that comes out to about 4 people each day. Sundays were usually when people came out with their best outfits, so we took advantage of that and snapped 10+ people, which made weekdays much easier when we only had to take about 2~3 people.

一ヶ月に一冊作ればよかったので、一ヶ月で80人ぐらい撮ってました。一ヶ月の内20日間撮影に行ける計算で一日4人ぐらい。特にオシャレできる時期の日曜日っていうのがあったんで、そういう時は10~人の写真を撮って、平日は2~3人ぐらいみたいな。

Where in Harajuku did you go to take snaps of people?

原宿でスナップを撮る時はどういった所を見て回ってましたか?

I didn’t have a go-to spot. I just took photos of people with style and anyone interesting. I suppose you can say it was all by instinct.

特に見てなかったなあ。オシャレだという事と面白い事をやってるなと思ったら撮るみたいな。直感でしたね。

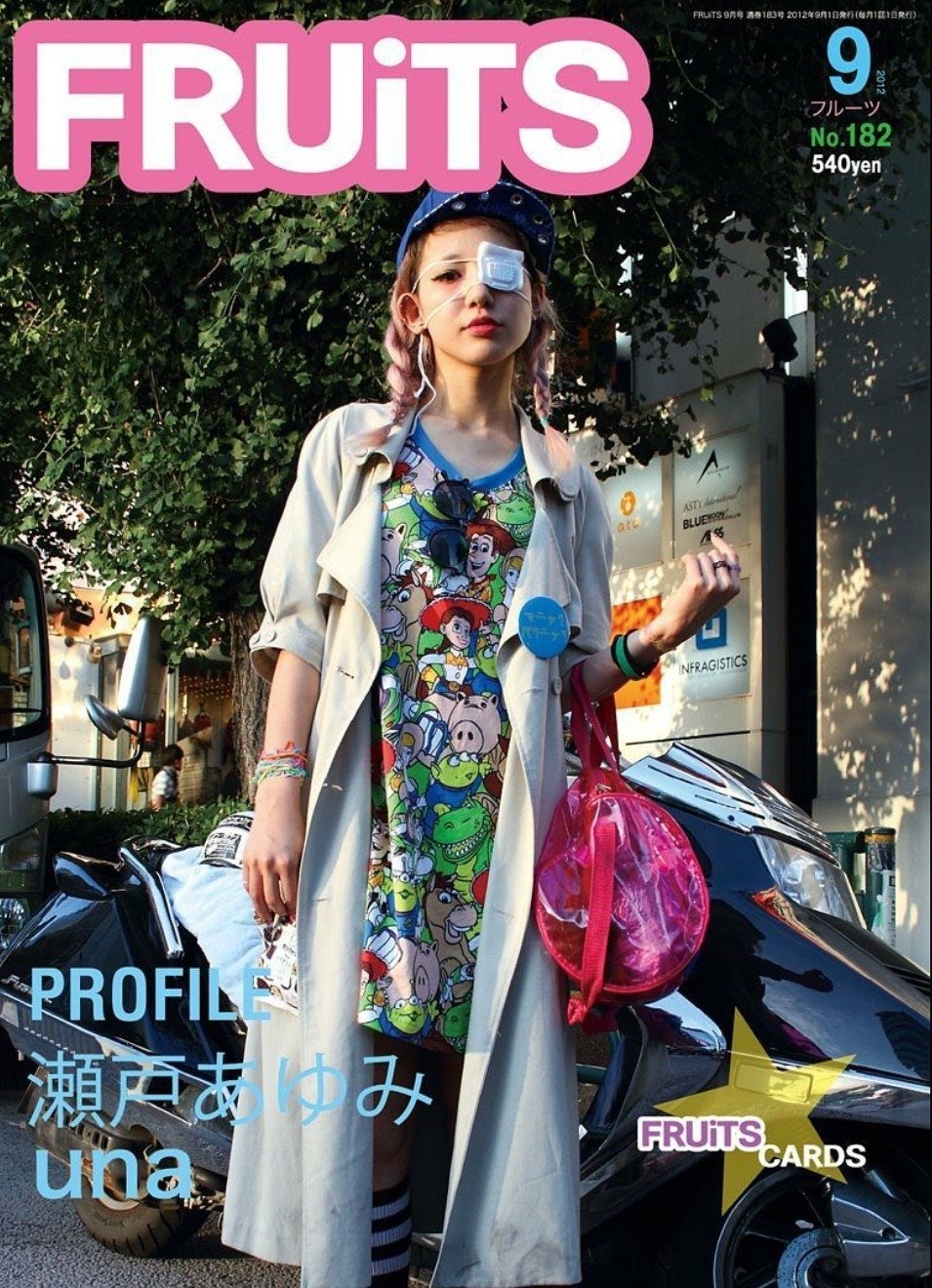

You’ve been keeping a close eye on Japanese youth culture since you started FRUiTS in 1997 until it’s final issue in 2017, how has fashion changed over the past decade?

FRUiTS を始めてから2017年まで原宿のユース・カルチャ―を目の当たりにしてきたと思うんですけど、どういう変化があった印象がありますか?

Harajuku fashion as we know it today started just around the time FRUiTS came to be. It took us about half a year to publish our first issue, so when we finally did release the magazine, Harajuku was really popping. Five years after that, people started to wear simple clothes to sort of counteract the loud and extravagant style found in Harajuku, and I think that continued for the next five years, as well… Most of the boys switched to the Urahara style as soon as that was a thing, and Urahara dominated the scene forever [laughs].

A lot of kids started dressing frugally or minimalistic for a short time, but a lot of the kids also preferred the Urahara style. Girls were dressed like how Kyary Pamyu Pamyu dressed before she became a global sensation, but at the same time, this magazine called mini was curating frugal styles and kids were really digging it. Harajuku started to feel like Daikanyama in a sense, and that was also around the time I started thinking about quitting the magazine. That’s when I remembered I didn’t really start this magazine just to take photos of people in Harajuku, but I rather wanted to keep this as a record of street fashion as it evolved. I still couldn’t get myself to take photos, so I got my staff members to take the photos, instead.

Japanese talent Kyary Kyary Pamyu, whose look was often copied on the streets of Harajuku during the 00s

Then, fast fashion became a thing, and if I remember correctly, Forever 21 was the first brand that came to Japan. I might even remember another British brand that came before Forever 21, but fast fashion sort of ruined fashion for me. I just didn't find fashion that interesting anymore, but after a while, I found the clothes and styles Chinese tourists in Japan were wearing quite interesting. This was around the same time VETEMENTS and Off-White by Virgil Abloh were starting to catch mainstream attention, and they ultimately became the force that ended the fast fashion reign. People like to hate on these brands, but I think they were key actors in toppling the fast fashion cultural landscape we were in for so long.

It’s unfortunate how the Japanese never really got on the VETEMENTS and Off-White hype, but it’s interesting how the Japanese started to wear loud clothes right after the Chinese tourists started to dress in Off-White clothes head-to-toe. I was excited about how things were going to turn from here, but then the pandemic happened.

大きな流れで言えば、原宿で見られたファッションっていうのは FRUiTS を初めて結構すぐだったんですよ。それで雑誌を出版する為の編集だったり準備に半年ぐらい時間がかかっちゃって、一冊目を出した時には結構盛り上がってて。それから5年ぐらいして逆のシンプル・ブームみたいなのになったんですよ。それがまた5年ぐらい続いたのかなあ?男の子は FRUiTS を始めた途中ぐらいからみんな裏原ファッションになって。それからずっと裏原《笑》。

シンプルな恰好をする子が結構いた時期も続いたんだけど、それから純粋に裏原っぽいファッションが戻りつつあって。象徴的なのはきゃりーぱみゅぱみゅがデビュー前にしてた変な恰好が流行ってたんだけど、シンプルな恰好も mini っていう雑誌が当時で出始めて「シンプルっていいよねえ」みたいな感じもあって。その頃にファッション的に原宿が代官山みたいな感じがし始めたんだけど、特に面白くもないなあと思って雑誌を辞めるかどうするか悩んだの。でも元々原宿の FRUiTS 的なファッションを撮りたくて始めたわけじゃなくて、ストリートファッションを記録する媒体として見てて、それをやろうと思って始めたんですけど、僕撮れないなあと思ってスタッフが撮る様になったんですよ。

それからファストファッションが流行り始めて、最初に Forever21 が来たのかなあ?その前にイギリスのブランドもあったんだと思うんだけど、ファストファッションブームが来たぐらいからファッション自体面白くなくなっっちゃって。その後の世界的なファッションの流れと中国観光客のファッションが面白いと思ってたんだけど、丁度その頃 VETEMENTS とヴァージル・アブローの Off-White がずっと続いてたファストファッションを断ち切った。結構批判する人もいるけど、そういったブームを断ち切るための大きな要因がこの二つのブランドにあると思ってて。VETEMENTS はともかく Off-White なんかはあまり日本人に飛びついてなかったんだけど、中国人観光客は全身 Off-White で包む様な中々できない恰好で歩いてたけど、それに触発される感じで日本人のファッションも思い切った恰好をする様になったかなあと思ってた時期があって。これから面白くなるかなあって期待してた矢先にコロナ禍が始まっちゃって。

What time period was the “highlight” for you, in terms of taking street photography?

様々な時代のファッションを見られてきたと思うんですが、その中でも特に撮ってて楽しかったのはいつ頃のファッションか?

I think it was most exciting when I first started FRUiTS [during the late 90s], and it didn’t get much better from there [laughs].

最初に FRUiTS の写真を撮り始めた時期だけかも《笑》。

Can you explain what makes Harajuku so special in one sentence?

原宿の何が特別か、一言で説明してもらってもいいですか?

People in Harajuku have nothing else but style and flare in their heads [laughs]. There aren’t a lot of people like that, but Harajuku is full of people like that [laughs].

オシャレな事しか考えてない子だらけ《笑》。中々そういう子はいないけど、そういう子しかいなかった《笑》。

Where is your office located now?

今の事務所はどこら辺にありますか?

Our office is quite nearby, but it used to be just above this Dr. Martens store in this old building, and we’re turning it into a gallery space. We want to do a lot of cool stuff with the space, and one of the things we’re thinking of doing is turning it into a private gallery for the STREET team. We were able to book Anders Edström, a photographer close to Martin Margiela. He doesn't have a lot of photos, but he has a lot of behind-the-scenes snaps, and never-before-seen photos of Martin, which he is debuting at our gallery. They come in different sizes, but he’s only printing 3 editions for each of the photos he’s exhibiting for the show.

今の事務所はそこのローソンを過ぎた所にあるんだけど、昔 Dr. Martens があったお店の上に事務所があるんですけど、今度ギャラリーになります。色々やりたいんだけど、STREET 編集室のプライベート・ギャラリーみたいな感じで、9月3日から Anders Edström って Martin Margiela の友達の写真展をやる予定で。写真自体はちょっとしかないんだけど、Martin の写真と彼のショーの写真をギャラリーで見せるのは初めてらしくて。一般公開で多くの人に見てもらって更に結構お手軽な値段で購入できる形も考えてて。大きいのから小さいのがあるんだけど、それぞれエディション3で三枚しか刷らないみたいだから。

Pop stars like Gwen Stefani were under fire for appropriating Harajuku style in the early 2000s. What do you think about how much global attention Harajuku got during this time?

2004年辺りは Gwen Stefani がハラジュク・ガールズを結成するなどして世界的に原宿が注目の的になったと思うんですけど、その時期について少しお話してもらってもいいですか?

I actually didn’t know who Gwen Stefani was at the time, and people used to ask me about her all the time, but neither did I know or care enough to say anything about it [laughs].

当時 Gwen Stefani の事を知らなくて、昔もよく「どう思う?」って聞かれたんですけど「知らない」って《笑》。

Do you think Harajuku will ever capture the attention of the world like it used to?

最盛期みたく、これから原宿が再熱する事はあると思いますか?

I don’t know. I myself hope something springs from Harajuku again, but I suppose it’s easier said than done. Heaven by Marc Jacobs was pretty interesting in that it almost felt like a new wave was swelling, and the fact that people are itching to dress up and go out makes me hopeful that we’ll get to see more genuine Japanese styles. Although I must say, it’s a bit too anime. Back then, Harajuku fashion influenced outfits that were worn by anime characters, but it’s the opposite now.

I didn’t know celebrities like Lady Gaga were influenced by Harajuku fashion, but I remember a lot of brands and labels were taking note at some point in time. I remember watching an interview with Karl Lagerfeld when he was working for CHANEL, and he was asked what he thought about Harajuku fashion. He admitted how everyone was copying Harajuku style, and to my surprise, he mentioned how he used to read this weird magazine that exclusively took Harajuku-inspired fashion. I was appalled and flattered to find out Karl Lagerfeld of all people used to read FRUiTS [laughs].

どうだろうねえ?そればかりはなってほしいと思うんですけど、デリケートなので何かがやってきて萎んじゃうんだよね。コロナ禍の最中に Heaven by Marc Jacobs で何かと流れが生まれた時にも感じたし、今となっては自粛を諦めてみんなオシャレしだしてるんで、中国人観光客のファッションが混じってない純粋な日本人のオシャレな人のファッションが増えてて。それはそれで面白いと思うけど、結構アニメっぽくなってるよね。昔は原宿ファッションがアニメのファッションを影響してたんだけど、今はその逆でアニメのファッションが流行ってるよね。

Lady Gaga が原宿のファッションを彼女のスタイルに取り入れてた時期があった事は知らなかったんだけど、結構色んなブランドが原宿ファッションを取り入れちゃってた頃があったみたいで。こないだ亡くなった CHANEL のデザイナーをやってた Karl Lagerfeld が「原宿ファッションについてどう思いますか?スタイルに取り入れてますか?」って聞かれてて「みんな取り入れてるよねえ。僕もちゃんと注目してるし、原宿のストリート・ファッションだけを載せてる変な雑誌もあって、みんな読んでるよ。」って言って、彼が読んでくれてる事実が面白かったし、嬉しかった《笑》。

You caused a phenomenon in Harajuku called *“Aoki-machi,” people waited for you to show up so they could have you photograph them. Can you tell us a little bit more about what exactly happened?

*Editors note: “Aoki-machi” is a play on Shoichi Aoki’s last name and the Japanese word for “waiting” which is machi/待ち.

「青木待ち」と言われる現象が起こってたと聞いているんですけど、それについて少しお話お聞かせください。

I didn’t know about this myself, but Masuda-san of 6%DOKIDOKI claims that was a thing. Back then, most magazines that took street snaps used to wait in a specific spot to take photos, but that just didn’t work for FRUiTS. People knew who we were, but more importantly, camping in the same spot would’ve bred ground for wannabes scaring the cool kids away. That’s why we walked around town instead of creating a designated spot, and I just took photos of kids I thought were cool [laughs].

I know that some kids actually came out to town looking their best to have their photos taken, but I usually didn’t like their style. A lot of the kids who look like they tried don’t have the taste and skill to actually style themselves properly, so they end up looking like try-hards. That’s why I didn’t take their photos [laughs].

Models wearing 6%DOKIDOKI, a brand popular with the Decora Fashion community.

僕も知らなかったんだけど、6%DOKIDOKI の増田さんがそういう事があったって言ってるんですよ。当時他の雑誌は場所を決めて、どちらかというと待ってて、そこに人がやってくる状態を作り出そうとしてて。今もそんな感じなんだけど、当時の

FRUiTS がそんな事やってたら大変な事になっちゃってたし、ダサい子しか来ない状態になっちゃうから、どちらかというと場所決めないで歩いてたんですね。だから逆に撮られたい子は座って待ってて、僕が通って気に入ったら撮って、気に入らなかったら撮らないみたいな《笑》。だから「オシャレして青木さんに撮られに行こう」みたいな感じはあったみたいなんだけど、そう考えると僕の趣旨とはずれてて、逆に撮らない事の方が多かったかもしれない。撮られるために頑張ってオシャレしてきたみたいな子は、そこまでやってオシャレになる技量を持ってる事が少ないので、大体ダサくなっちゃうんですよ。だからバツ付けて通り過ぎ《笑》。

Back then when social media was not a thing, influencers were a rare sight. Now that the internet and fashion are so intertwined, it’s hard to imagine how things would look like without the internet. How do you think the internet has influenced fashion as a whole over the years?

当時はまだ SNS も普及してなくてインフルエンサーも見えなかった時代だと思うんですけど、今やネットありきのファッションと言っても過言ではない程切り離せないものになってますね。インターネットはファッションにどういった影響を与えたと思いますか?

Just before social media became a thing, there were about 3 media outlets that straight up ripped off FRUiTS. They weren’t even hiding the fact that they were ripping us off, but I think only one survived in the end. FASHIONSNAP.COM grew pretty big over the years, but they also had to change direction to cover fashion news rather than exclusively taking street snaps. I also understand that street snaps have become a sort of genre in social media, but I don’t know much about what’s going on there, to be honest.

丁度 SNS が普及する前にネットで FRUiTS のパクリみたいな媒体が3つぐらい出てきて。彼らは明確に FRUiTS をパクったネット版である事を露わにしてたんだけど、結局残ったのは一つだけかな?FASHIONSNAP.COM は多少大きくなって途中で路線変更してファッションニュースを伝えるメディアになって。今もスナップはやってるのかな?後は SNS で自分のファッションを載せる子が多くなってるけど、そういう中で生活してる子たちの気持ちはわからないですよね。

How do you think things will change from now onwards?

今後はどう変わっていくと思いますか?

I don’t know. I suppose people are finally able to go out and flaunt their outfits after being stuck at home for such a long time, so it’s interesting. The manufacturers, on the other hand, I’m a bit worried about not so much for high fashion labels that have enough capital to power through these things, but rather the medium to small-scale brands that have to make decisions just to survive. They just have to come out with clothes that are digestible for the mass market to generate sales, but in hindsight, I’ve come across kids with good taste that have the ability to turn the mundane into something with flair, so I’m excited. I hope these brands figure it out because street fashion is so dependent on them, but so long as we don’t go back to fast fashion, I’m quite hopeful things will turn around.

どう変わっていくんだろう?どちらかというとコロナ禍でできなかったファッションをいい加減なんとかしたいよねっていうのでしだしてるファッションなのかなあ。でも作る側/ブランド側は元気がないよね。資金力のあるハイブランドなんかは大丈夫だろうけど中堅のブランドは売るのも表現するのも大変だろうから、街にいる若い子がオシャレしたくなる様な洋服が先に出てる感じかもしれない。そういう意味でわかりやすいところに飛びついてる感じは強いかもしれないけど、結構スタイリングの観点で凄い才能ある子もいるので良くなっていくかな?ブランドが元気ないとストリートファッションも面白くないので、ファストファッションみたいな変な動きがなければ面白くなっていくかもしれない《笑》。

How big of an issue was the pandemic for the street fashion scene?

やはりコロナ禍のストリートファッションへの影響は大きいですか?

Well, first of all, people weren’t allowed to go into town. We only got to go outside recently, but the last 2 years were detrimental to the industry, so I think the more unique brands that cater to niche communities will continue to disappear. I heard PUNK CAKE is closing its doors soon, and it’s a shame because these were the stores that made Harajuku, Harajuku. As you can imagine, after these stores get kicked out, it’s mostly big brands and sneaker stores that come in to take their place.

まず街に出なくなったのが大きいよね。本当に最近になって街にオシャレして出る様になったから、二年間ぐらいそれが止まっちゃってたよね。今まで大変だったけどこれからもっとお店が潰れていくだろうから、個性的な原宿のお店はどんどん無くなっていく。パンクケイクも今度辞める事になったみたいだし。原宿は個性的なお店が造ってた街でもあったので、そういうところが経営が厳しくなって辞めていくと、その後に入ってくるのはお金のある大きいところかスニーカーをやってるお店だよね。

The interior of Punk Cake a beloved Harajuku select shop.

What were some of the hottest and most memorable brands back then that you can recall?

当時才能があって勢いがあったという印象を受けたお店ってあったりしますか?

There were a lot of them, but they’re mostly out of business. They came in guns blazing, and went out of business just as violently.

ブランドもショップもいっぱいあったけど、もうほとんど無くなっちゃったよね。ドーンって行ってドーンって無くなっちゃったみたいな。

The puffy masterpieces of Tomo Koizumi, a designer Aoki-san admires.

Do you admire any contemporary brands or anyone’s clothes?

今は特に印象に強く残ってるブランドはあったりしますか?

I like people who make their own clothes, so I find a lot of contemporary designers quite talented, however, to be honest, I’m not that interested in them [laughs}. I have friends who make clothes, and some of them are doing cool things, but I don’t really know anyone who has what it takes “to take on the world”. Harajuku has been dry these past few years in that sense, but otherwise, I think TOMO KOIZUMI might be the only one I really admire.

僕が才能があると感じるのは、どちらかというと自分のファッションを作る子たちなので、デザイナーとかをやってる様なところには常にいると思うんですけど、正直あんまり興味ない《笑》。仲良くなったりするし、凄いと思う子もいるんだけど、世界的に見ても凄いと思う子はそんなに出ないよね。原宿からは全然出てきてないけど、今は TOMO KOIZUMI さんぐらいかなあ。

The 2010s saw the gradual decline of Harajuku, is that correct?

2010年以降から原宿も衰退期に入っていった感じですよね。

Yeah, and it’s mostly because of the rise of fast fashion. 10 years of that crap was enough reason for me to shut down FRUiTS.

さっきも言ったかど、ファストファッション・ブームも10年ぐらい続いたもんねえ。それで FRUiTS もやめちゃったしねえ。

When exactly did you decide to shut down FRUiTS for good?

FRUiTS 自体を終了させようと決断を下したのはいつ頃でしたか?

I’ve mentioned this on multiple occasions, but I just couldn’t find kids with style anymore. I’m not saying they disappeared all of a sudden, but like I mentioned earlier, we had to take 2~3 snaps of different people a day to compile 80 different styles a month. We even switched to bimonthly releases, but we simply couldn’t find that many even then. 5 years had passed since I delegated the street snaps to my staff members, and we had about 3 people out on the streets on shoot days, but considering how little photos they got each time, it just didn’t make sense for me to continue [laughs]. It’s not like we had an unlimited supply of money to fund this, you know [laughs].

他の取材でも言ってる通り、オシャレな子がいなくなっちゃったんで。ゼロではなかったけど、さっき言った様に一ヶ月に80人、一日に2~3人撮らないと雑誌にならないんで、月間やめて隔月にしたりしてたんだけど、それでも見つかんなくて。それからスタッフも雇えなかったし。当時僕が撮影をやめて5年後ぐらいからスタッフがやってたんだけど、平均3人ぐらいいたんですよ。毎日写真を撮ってたんだけど、それを仮にやり続けてても「いませんでした。」みたいな日が続いただろうから《笑》。それじゃあ何に金払ってるのかわかんないじゃん《笑》。

You mentioned how there were a couple of websites that ripped off FRUiTS back then, but nowadays the whole concept you founded, is an entire genre on Instagram and fashion journalism. How do you feel about this?

先程仰ってた FRUiTS のパクリが当時ではじめて、今となってはインスタグラムでは同じ様なコンセプトがジャンルとして流出してますが、これに関して思う事はありますか?

I didn’t really think much of it back then. This was just before fast fashion took off, and a lot of interesting things were happening, and if I had just figured out how to make money out of it, I would’ve made something instead of printing physical magazines since I preferred digital media. It’s not the easiest thing printing magazines, you know [laughs].

There’s a lot of labor involved in making a magazine, from physically taking the photos to editing them on the computer, and finally printing them on paper. The whole process degrades the quality of these images, and I rather think keeping it digital prevents that from happening. It’s quite different when it comes to physical prints since you have to think about the different systems each machine has in place, so it affects how you edit the photos, and all of these things add up to creating something that's good enough for people to physically consume. To be honest, it was becoming quite stressful for me toward the end of FRUiTS. If I knew how to, I would’ve continued taking street snaps and put them on the internet, but I’ve yet to come across anyone who’s made a living off it in Japan.

I’ve talked to Koyama-san from FASHIONSNAP.COM about this, and he was eager to fund my project so long as I find a way [laughs]. Although, they eventually pivoted to cover fashion news, and street snaps have sort of become a marketing tool for them. Scott Schuman’s work is a great example of what I want to do, but the U.S. has about 10 times the market size of Japan, so it was easier for him to find ways to monetize his content, and I’ve envied the fact that he was born in an English speaking country. It’s almost absurd, but no one’s really figured out a way in Japan yet.

I recently visited London for a shoot with THE FACE magazine, and I checked out this bookstore. I saw an aisle filled with local magazines, and I was surprised to see how expensive some of these magazines were. It seemed like they were on a seasonal release schedule, and they had different covers for the same issue, and I guess that’s how they’ve come to justify the nearly JPY 2000 price tag. There were a lot of high fashion label ads in these magazines, and comparing them to how Japanese magazines are still operating today, I was convinced how backwards we were.

当時はどうも思ってなかったかなあ。やれるならやりたかったですけど、お金にできないよなあと思って。時期的にはファストファッションのちょい前ぐらいの時で、ファッション的にも面白い時期ではあったんだけど、僕もどちらかというと紙の雑誌よりもパソコンとかデジタルなものの方が好きなので、そっちで良かったならそっちでやりたかったね。紙の雑誌を作るのは大変なんだよね《笑》。被写体見て、写真撮って、パソコンで加工、印刷するっていうステップを踏むと全部劣化してくの。写真をデジカメで撮って、そのままパソコンで見るとイメージがそんなに劣化しないと思うんだけど、紙に刷ると色のシステムも違うし、加工の工程も違うから、紙で満足させるのは結構大変で、FRUiTS の最後辺りでは結構自分のストレスになってた。今でもそうなんだけど、僕がやりたかったストリートスナップをネットに上げてやってもお金にできないよなあと思ったし、誰もやってなかったFASHIONSNAP.COM の光山さんに話した時に「お金になる方法を見つけくれたら僕がパクるから、早く見つけてよ」って言って《笑》。それで彼はファッション・メディアの方に行っちゃったんだけど、結局ストリートスナップは集客のツールとしてしか使われていないという形になっていって、でも僕としてはそういったマーケティング・ツールではないから。アメリカでストリートスナップを始めて有名になった Scott Schuman なんかは英語圏だとマーケットが10倍以上あるので、写真をネットに載せるだけでもマネタイズの方法っていうのが生まれてくるんだけど「アメリカ人だったら良かったなあ」とかって思ってて、それが今でも同じで。日本じゃまだ誰もストリートスナップをマネタイズする方法を見つけられてない。

ファッションウィークでも何十人もフォトグラファーがいるものなんだけど、昔は僕一人しかいなかったから「一人で寂しく何やってんの」ってよく言われたし。ショーを撮るフォトグラファーは何十人もいるのに「なんで外でしか撮らないの、青木君」って言われて《笑》。「外の方が面白いじゃん」って言ってたんだけど、今は逆転してショーを撮るフォトグラファーより外のスナップを撮るフォトグラファーの方が多くなってて、未だにどうマネタイズできるかよくわかんないんだよね。割り切って完全案件の方針でやるのも手だけど、それじゃあメディアみたいな感じになっちゃうし。っていうところで FRUiTS がまだスタートできてないんだよね。紙を流出する時代は終わっちゃってるしね。

こないだ25年ぶりぐらいにロンドンに行って、THE FACE マガジンの撮影をしてきたんですよ。それで本屋さんみたいなところに寄ってみたら雑誌が並んでたんだけど、一冊2000円ぐらいして高いんだよ。月刊というより季刊に近い感じだし、表紙も一号につき3~4種類ぐらいあったりして、みんな大体そういう風にやってるみたいで、なんか新しいビジネスモデルを見つけたのかなあと思わせられたの。それから中見てみるとハイブランドの広告があったりするんで、逆に日本は昔のまんまで潰れていってるからねえ。

Most Western magazines have a seasonal release schedule, and while a bit expensive, the quality matches the price. It feels as though monthly releases are unique to Japanese magazines these days.

アメリカなんかでも季刊に近い形で色んな雑誌が出されていると思うんですけど、日本と比べて値段が高いけど紙の質が高かったりしますよね。未だに月々安く出しているのは日本特有のイメージがあったりしますね。

I think they too were on a monthly release schedule before paperback was obliterated by the internet. I remember THE FACE used to sell their thin magazines for around JPY 500, but they had to go through a reformation to survive, and that’s how we ended up with thick and expensive seasonal magazines. Japan is so adamant on keeping things the way they were, and it feels like they’ll continue to do so until they all die. Everyone asks me to start running FRUiTS again, but I know for a fact they won’t buy them [laughs].

多分紙の雑誌が駄目になる前は一緒だったと思う。みんな月刊で出してたんだと思うんだけど、THE FACE マガジンなんかも500円ぐらいの薄いものを出してたの。ファッション誌全般的に駄目になって改革が今の季刊の分厚い形を作ったんだと思うんだけど、日本がその新しい風に乗れないで取り残されているのかなあって。このまま昔のやり方を続けて全部無くなっていくんだろうなあって思う。みんな FRUiTS 再開してくれっていうんだけど「買わないだろう!」って思う《笑》。

You’ve mentioned how FRUiTS magazine has fast fashion to thank for its demise, but when did you start flirting with the idea of restarting? Are there any particular events that reignnited “the fire” for a FRUiTS revamp?

2017年に FRUiTS を終了させた背景にはファストファッションの影響が大きいという話をしてたと思うんですけど、また始めようというメンタリティにさせたキッカケとなるエピソードはあったりしますか?

I’ve come across more and more stylish kids as of late. Like I mentioned, fast fashion made it so that I almost never saw these people [laughs]. Back then, we had such a hard time finding kids with even an ounce of style in them, we had to snap the same people over and over for the magazine cover. It was usually the adventurous kids that made it to the cover since I just thought it would be a shame not to put their outfits down in some type of record. I also used to take photos with my phone, but I haven’t been doing so for the last two years, so I’m not sure where these photos are now [laughs]. I’ve been thinking of publishing a book that compiles all these photos I’ve taken over the years, but I haven’t figured out how I can connect it with my socials yet, so I’ve been looking for someone who knows what they’re doing [laughs].

There’s this English guy who’s been helping me with my socials, but he’s in Saudi Arabia right now. He used to publish comic books and he approached me with an idea to make an app for FRUiTS just like Shonen Jump does. I don’t know how this will turn out, but he’s also the one running the archive pages on Instagram, so I’ve a bit of faith in him.

ちょっと良いなと思える子がまたではじめたので。ファストファッションの到来でやめようと思った時なんかは本当に一人もいなかったの《笑》。その当時は本当にいなくて、表紙なんかは一番いい子を載せてたんだけど、一時期は何人かで回してたからね。でも「凄いなこの子」っていう子が時々出てきて、そういう子がいるかいないかで結構大きいのよね。やっぱり冒険/挑戦してる様な子がいたので、そういう子はフィーチャーしたいと思ったし、誰にも気付かれず消えていくのは勿体ないなあと思ったので記録して残していかないとって思って。「インスタに載せとく」って言っといてスマホで撮ってたんだけど、ここ二年ぐらい使ってないから全然載ってなくて《笑》。でもそういう写真を集めた本を作ろうと思ってて。でもインスタと紙の媒体の関係をどうしたらいいのかわかんなくて、そこを完璧に把握してる人に聞いてみたいぐらいで《笑》。

今イギリス人で、サウジアラビアに行っちゃったんだけど、お手伝いしたいって子がいて。彼は元々コミック関係のお仕事をしてたんだけど、少年ジャンプのアプリみたいに FRUiTS をやったらどうかって色々やってて。どうなるかわかんないけど、今インスタのアーカイブのアカウントも彼が回してるんだけど、データも全部あげて「勝手にやって」みたいな。

You’ve mentioned how you take snaps of people with interesting styles with your phone, do you ever mention who you are to them?

ちなみにスマホでたまに面白い事をやってる子を撮ると仰ってましたが、そういう時は FRUiTS の創業者である事を露わにしてから撮るものですか?

Yeah, but surprisingly, they know who I am [laughs]. I do have to admit, a lot of the teens these days have no idea what I do.

そうそう、一応 FRUiTS って知ってるんだよねえ《笑》。知っててくれると話が早いんだけど、やっぱり10代は知らない子の方が多いかなあ。

With the rise of social media and global trends spreading faster than ever, it seems like personalities and sensibilities unique to cities and regions are forgotten in favor of fitting in with trends. How do you think street fashion will evolve from here?

ネットと SNS が普及してからどこにいてもどの国のファッションが見れる様になって意識せずとも影響される事があり得ると思ってるんですけど、昔は都市間の個性が強かったのに比べて今は薄れているのではないかと感じています。これからのストリートファッションはどの様に変化していくと思いますか?

I’m not sure. But Harajuku seems to remain true to its style. London has quite the stylish bunch, but they dress nothing like Harajuku. Actually, there were a few kids who were dressed in Harajuku-inspired outfits in London, too.

I came across this Chinese girl who was visiting London, and she was dressed in this traditional dress. Apparently, it’s quite trendy there, but she had this beautiful green dress, and it’s one of my favorite photos I took during that trip. In that sense, I don’t think all the different cities will assimilate to what’s trendy on the international level. Even the kids dressed like they came from Harajuku are probably in the minority rather than the majority, you know [laughs]. London will always feel like London and Harajuku like Harajuku.

どうだろうね。でも原宿は原宿っぽい。こないだロンドンに行って「良いなあ」と思って帰ってきたんだけど、原宿は原宿っぽくて良いなあと思ったの。でも確かに原宿っぽい恰好をしてたロンドンの子もいた。こないだロンドンに行って撮ってきたものの中で一番受けたのは中国人の子の写真で、遊びに来てたんだけど、昔の官服みたいな、昔の中国の服が流行してるみたいで。緑色のドレスを着てて物凄く可愛かったの。だからそんなにスタイルは一緒にならないんじゃないかなあと思う。仮に原宿っぽい恰好をしてても、凄く変わった人しかしないじゃん《笑》。やっぱりロンドンはロンドンで原宿は原宿みたいな。

What's the future of street fashion, in your perspective?

ストリートファッションの今後についてはどう思われていますか?

I think London and Harajuku are the most exciting places for street fashion now, and although Paris has a lot of interesting people during fashion week, people aren’t that stylish otherwise. I do come across really interesting styles from time to time, and it’s similar to how it is in New York. Either way, I do think it’s going to get more interesting from here onwards [laughs]. Not suddenly, but slowly.

ストリートファッションの面白いところってロンドンか原宿ぐらいで、パリなんかはファッションウィークは面白い人が集まるけど、普通に歩いてて見つかるもんじゃないし。たまにメチャクチャ面白い人もいるけど、ニューヨークも同じ感じで。でも多分これからもっと面白くなると思う《笑》。急激には変わらないだろうけど普通に。

Outside of Harajuku, which areas do you find interesting to take photos in Japan?

日本だと原宿以外で面白いと思える場所はあったりしますか?

I’m not sure about these days, but Osaka used to be a lot of fun for taking pictures. It was at its peak when we first started FRUiTS. It was just completely different from Tokyo, and people used to wear wild outfits out of repurposed kimonos. There were plenty of unique kids around Tokyo, but Osaka was just wild, but the difference in characteristics between cities lessened over the years. I am hopeful that more people are going to dress as they please since media outlets these days don’t really have influence over style and fashion anymore. I just have a feeling that regional fashion and style are making a comeback in Japan. Otherwise, I think China is going to be interesting, but we’ll have to see the pandemic come to a close first.

最近はよくわからないんだけど、大阪は時々面白くなるよね。FRUiTS を最初にやり始めた頃はメチャクチャ面白かった。みんな東京とは全然違う恰好をしてて、本当にタケオエンジェル とか着てる子がいっぱいいたし、着物をリメイクしたものも着てた。東京には数人、大阪には何十ニ人っていたんだけど、そういった国内のファッション的な地域差ってドンドン無くなっていった。でも今また生まれるかもね、メディアがないから。ネットはあるけど、そんなにファッションを統一する力はないんじゃないかなあと思ってて。行ってみないとわからないけど、地域的なファッションが生まれてきてる予感がしてる。それから国外だと中国は面白くなるかもしれない。今はコロナ禍で止まっちゃってるけど。

You dress quite simply compared to the people you take photos of. Are there any particular reasons for this?

被写体とは対立的に青木さんはシンプル目な服装をしてる事が多いですが、これには理由はあったりしますか?

I don’t really have a reason to dress up [laughs]. I’d rather feel the breeze during summertime, and I put on denim pants for winter [laughs]. I’ve always admired Martin Margiela’s stuff, so I do have quite a lot of his clothes.

オシャレする理由がないから《笑》。夏は涼しさしか考えてないし、冬はとりあえず下はデニムで《笑》。ブランド的には Martin Margiela で止まってるんだよね。Martin の物は結構色々持ってる。

A Margiela inspired look captured in Aoki’s street snap shot.

You’ve not only met Martin Margiela, but you’ve also expressed your respect for him on multiple occasions. In your opinion, what makes him so great?

Martin Margiela 本人と会われたり、他のインタビューでも彼を絶賛されてますが、Martin の何が凄いのか少し教えてください。

He’s just on another level [laughs]. Like Coco Chanel and Rei Kawakubo, he changed the world, and I think that’s why I’m so drawn to his work. I also published a book that’s a compilation of his early work from 1995-2000, and that was a first in Japan. The reason I even decided to make a book on him is because even 5 years after his debut, people couldn’t stop talking about him, and although we used to get his collections hung in UNITED ARROWS and fancy department stores in Japan, no one had a clue how to wear them. Photographers and designers who went to fashion week were stealing all his ideas, and it just felt wrong, so I decided to publish a book on his collections to educate people, as well.

I’ve been taking photos since his second or third show, but I couldn’t get in the venue since there were too many people inside. I asked him if he could lend me some of his photos, but Martin decided he wanted to take the photos himself, so I just said, “sure.” [laughs] He had plenty of photographers around him, but he happened to ask a complete novice to start taking photos. I don't really know Anders’ relationship with Martin, but that guy became the other main photographer. There were about 5 photographers in total, and although they had a lot of photos, they never got the chance to show them to the world, so that gave me a reason to publish it in the book as well.

The book Shoichi Aoki produced with Noriko Kojima chronicling the early works of Martin Margiela titled “メゾンマルタン マルジェラストリート スペシャルエディション ブック1&2 1989-1999”.

桁が違う《笑》。Coco Chanel とか川久保玲と同じクラスで、世界を変えてるというところに惹かれたのかなあ。やっぱ桁違いですよねえ。1995~2000年に本を作ったのもあるんですけど、Martin の作品集としては一番最初のもので。そもそもなんでその本を作ったかというと、デビューしてから5年ぐらい経ってもパリコレ行ったら Martin の話しかしないみたいな時期なのに、日本に帰ると服は UNITED ARROWS にワンホールと資生堂のデパートにワンホールあったんだけど、どう着たらいいかわからない。パリコレだとスタイリストからデザイナーまでフォトグラファーも行って見てるんで、みんなパクり放題みたいな状態で「これはちょっと違うんじゃないの?」って思って、彼のコレクションの本を作る事に決めたの。

Martin の2~3回目のショーから撮ってたんだけど、途中から凄い人気で会場入れなくなったから彼に「写真貸して」って聞いたら、Martin が「自分で作りたい」って言い出して。それで「じゃあ作って」って感じで任せた《笑》。彼の周りに何人かフォトグラファーがいたんだけど、全然フォトグラファーじゃない人に「やってみない?」って声かけたみたいで。Anders とは元々どういう関係だったのかは知らないんだけど、最初から Martin とやってて、もう一人メインで撮ってた人はそんな感じでフォトグラファーになったんだよね。計5人ぐらいいたんだけど、ずっと撮ってきたものを世に出す機会が中々来なくて、自分が編集して出そうと思って。

The 1980s was just around when COMME des GARCONS and Yohji Yamamoto were at their peak, and although it must’ve been a fresh and exciting sight for foreigners, what was the general consensus in Japan?

1980年代は川久保さんや耀司さん率いる COMME des GARCONS と Yohji Yamamoto が凄く流行ったと思うんですけど、海外の方々の視点からしたら今まで見られなかったスタイルが新鮮に感じたられた傍ら、日本でスナップを撮ってた青木さんから見た国内の反応はどんな感じでしたか?

I wasn’t really taking photos in Japan yet, mainly around London and other foreign countries at the time. But I did wear their clothes. It was really something else, you couldn’t find anything like it elsewhere. I suppose brands like COMME CA DU MODE were doing a good job literally copying their clothes panel to panel, but I couldn’t wear their stuff. You can’t really tell the difference, but I just couldn’t get myself to wear them, so that’s why I was stuck with CDG’s and Yohji’s clothing [laughs]. Come to think of it, they weren’t really selling clothes, but rather suggesting ideals of beauty, and it was almost like a cult, to be honest.

当時はまだ国内では撮ってなくて、ロンドンとか海外主体にやってた。でも自分で着てた。本当にどこにもなかったスタイルだったから何処にも売ってなかった。他で買おうと思ったらギャルソンで買ったものを解体してパターンを取って服にした COMME CA DU MODE みたいなブランドしかなかったんだけど、そっちの方が儲かってたんで。見た目で区別できなかったんだけど、僕はちょっと着れなかったからギャルソンを着るしかなかった《笑》。当時は洋服というよりかは美意識そのものを買わされてた感じがあって宗教みたいだったよ。

Are you into any subcultures other than what you’ve seen while documenting fashion and in your photography?

ファッションとフォトグラフィーで活躍されてる青木さんですが、他に好きなサブカルチャーってあったりしますか?

At the time, I loved contemporary dance. I just watched it, but since there was no Internet or other information available at that time, I had a recording of it from American TV shows sent from the States to me. It was a program that featured various aspects of American culture, including contemporary dance, and it was really interesting. In return, I would send them tapes of Dragon Ball. Whenever I went to London or Paris, there were sometimes contemporary dance shows, and I liked it so much that I would go to see them. Now it's a genre of dance on TikTok, but at the time it was rare.

音楽なんかも結構好きなんだけど、聞き出すと一日中聞いちゃうタイプだから、ほとんど聞かない。

To wrap things up, do you have any words of advice for the younger generation?

若い子たちに向けて一言お願いします。

I don’t think I have any. You guys have it really good, the possibilities are so limitless it’s almost like a dream [laughs]. That being said, we're planning on making a FRUiTS museum on the web somehow, so that’s something you should look forward to.

特にないかなあ。頑張ってじゃないけど、あなたたちのいる環境は昔の僕からしたら夢みたいな話なので、なんでもできるよね《笑》。実は FRUiTS の美術館をウェブ上でやろうとしてるんですけど、まだ形になるものが見つかってない。

Interview by Casey Omori and Mizuki Khoury

Interview Edited by Ora Margolis

Introduction written by Ora Margolis

Article Formatted by Ora Margolis

Photography by Shirin